By Peter Alan Lloyd

A North Vietnamese 122 mm shell hits a U.S. ammunition bunker at Gio Linh, South Vietnam

Prince Norodom Sihanouk, left, in Phnom Penh, 1968.

Sensors dropped along the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Attapeu Laos

Truck traffic increased along the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos when the bombing of North Vietnam was halted.

NVA emerge from the jungle onto the Ho Chi Minh Trail

North Vietnamese soldiers ready an ambush in the Laotian jungle.

A heavily-armed Skyraider.

Unexploded BLU-26B cluster bomblets spilling out from a cluster bomb casing.

A BLU-3B cluster bomblet, aka The Pineapple

An air strike in the Laotian jungle

Skyraider pilot looks down having just made a close air strike

Door gunner of a Helicopter gunship of the 20th Special Air Squadron, making a low pass

North Vietnamese Army soldiers moving down the Ho Chi Minh Trail at night

122 mm North Vietnamese rocket being fired.

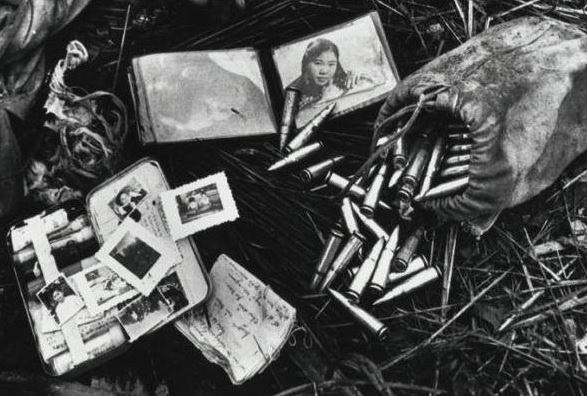

Detail of dead NVA’s possessions, 1968 (Don McCullin)

PAL: What happened at the extraction?

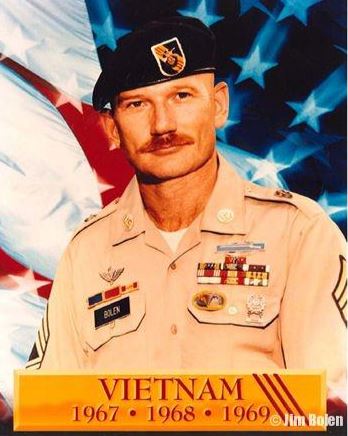

Mang Hai, Me, Nay Bunn (my interpreter), unknown, Mang Kaoh (my point man), unknown. RT AUGER 23, January 1968.

PAL: What happened when you got it back to base with the weapon?