Operation Daniel Boone

During 1966 and 1967, it became obvious to MACV that the North Vietnamese were using neutral Cambodia as a part of their logistical system, funneling men and supplies to the southernmost seat of battle. Unknown was the extent of that use. The answer shocked intelligence analysts. Prince Norodom Sihanouk, trying to balance the threats facing his nation, had allowed Hanoi to set up a presence in Cambodia. Although the extension of Laotian Highway 110 into Cambodia in the tri-border region was an improvement to its logistical system, North Vietnam was now unloading communist-flagged transports in the port of Sihanoukville and trucking the cargo to its base areas on the eastern border.

Beginning in 1966, SOG conducted prisoner snatch missions of PAVN soldiers behind enemy lines along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail. No matter the team’s primary mission, capturing enemy soldiers always remained the team’s secondary mission when the opportunity presented itself due to valuable intelligence gained related to PAVN troop movements, size, and base locations. Teams also received rewards including free R&R trips to Taiwan or Thailand aboard a SOG C-130 blackbird, a $100 bonus for each American, a new Seiko watch and cash to each indigenous member. Recon teams succeeded in capturing 12 enemy soldiers in Laos during that year.

In April 1967, MACV-SOG was ordered to commence Operation Daniel Boone, a cross-border recon effort in Cambodia. Both SOG and the 5th Special Forces Group had been preparing for just such an eventuality. The 5th SF had gone so far as to create Projects B-56 Sigma and B-50 Omega, units based on SOG’s Shining Brass organization, which had been conducting in-country recon efforts on behalf of the field forces, awaiting authorization to begin the Cambodian operations. A turf war broke out between the 5th and SOG over missions and manpower.[20] The Joint Chiefs decided in favor of MACV-SOG, since it had already successfully conducted covert cross-border operations. Operational control of Sigma and Omega was eventually handed over to SOG.

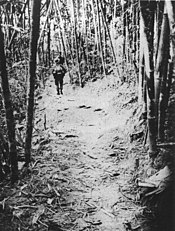

The first mission was launched in September and construction was begun on a new C&C at Ban Me Thuot, in the Central Highlands. The recon teams (RTs) inserted into Cambodia faced even more restrictions than those in Laos. Initially, they had to cross the border on foot, had no tactical air support (neither helicopters nor fixed wing), and were not to be provided with FAC coverage. The teams were to rely on stealth and were usually smaller in size than those that operated in Laos.

Daniel Boone was not the only addition to SOG’s size and missions. During 1966, the Joint Personnel Recovery Center (JPRC) was established. The JPRC was to collect and coordinate information on POWs, escapees, and evadees, to launch missions to free U.S. and allied prisoners, and to conduct post-search and rescue (SAR) operations when all other efforts had failed. SOG provided the capability to launch Brightlight rescue missions anywhere in Southeast Asia at a moment’s notice.

The Air Operations Group had been augmented in September 1966 by the addition of four specially-modified MC-130E Combat Talon (deployed under Combat Spear) aircraft, officially the 15th Air Commando Squadron, which supplemented the C-123s (Heavy Hook) of the First Flight Detachment already assigned to SOG. Another source of aerial support came from the CH-3 Jolly Green Giant helicopters of D-Flight, 20th Special Operations Squadron (20th SOS) (callsign Pony Express), which had arrived at Nakhon Phanom Royal Thai Navy Base during the year. These helicopters had been assigned to conduct operations in support of the CIA’s clandestine operations in Laos and were a natural for assisting SOG in the Shining Brass area. When helicopter operations were finally authorized for Daniel Boone, they were provided by the dedicated support of the Huey gunships and transports of the U.S. Air Force’s 20th SOS (callsign Green Hornets).

MACV-SOG reconnaissance teams were also bolstered by the creation of exploitation forces, which could either support the teams in time of need, or launch their own raids against the trail. They consisted of two (later three) Haymaker battalions (which were never used) divided into company-sized “Hatchet” forces which were, in turn, sub-divided into “Hornet” platoons. The commanders and non-commissioned officers of these forces were U.S. personnel, usually assigned on a temporary duty basis in “Snakebite” teams from the 1st Special Forces Group on Okinawa.

By 1967, MACV-SOG had also been given the mission of supporting the new Muscle Shoals portion of the electronic and physical barrier system under construction along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) in I Corps. SOG recon teams were tasked with reconnaissance and the hand emplacement of electronic sensors both in the western DMZ (Nickel Steel) and in southeastern Laos.

Due to the disclosure of the cover name Shining Brass in a U.S. newspaper article, SOG decided that new cover designations were necessary for all of its operational elements. The Laotian cross-border effort was renamed Prairie Fire and it was combined with Daniel Boone in the newly created Ground Studies Group (OPS-35). All operations conducted against North Vietnam were now designated Footboy. These included Plowman maritime missions, Humidor psychological operations, Timberwork agent operations, and Midriff air missions.

Never happy with its long-term agent operations in North Vietnam, SOG decided to initiate a new program whose missions would be shorter in duration, conducted closer to South Vietnam, and carried out by smaller teams. Every effort would be expended to retrieve the teams when their missions were accomplished. This was the origin of STRATA, the all-Vietnamese Short Term Roadwatch and Target Acquisition teams. After a slow initial start, the first agent team was recovered from the north. The following missions were plagued with difficulties, but, after additional training, the team’s performance improved dramatically.