Story Two of Two

By Manuel Beck

I arrived at Camp Ho Ngoc Tau Project SIGMA on April 29, 1968. I went straight to the camp’s Operations Center, where I received a briefing on the Area of Operations (AO) from the S-2 and a mission briefing from the S-3. The S-2 told me the AO was called War Zone C, which was west of the Tay Ninh Province in South Viet Nam. The forward launch site was being run out of an A-Camp called at Loc Ninh. The S-2 continued his briefing, saying they knew the 7th NVA Division and maybe one more Division were in the area across the border in Cambodia. He also said there was a large VC force with them, perhaps over 10,000 enemy troops in War Zone C. He told me that SIGMA had been running Recon missions in that area for over a year and had a large number of casualties. He continued with a lot of information and statistics. My head was spinning, trying to comprehend all that information, an unconventional warfare unit with a mission to conduct cross-border special long-rang reconnaissance were, gathering information and locating American Prisoners Of War (POWs) so they could be rescued, everything we did in that AO was Top Secret. After the briefing, I had to sign more forms stating I would never talk about what I did while assigned to B-56. This was nothing like what I had been trained to do at Special Forces Training Group, and the 3rd Special Forces Group. However, it would be exciting if I survived it.

The S-3 sent me to see the S-1. The S-1 took a photo of me to put in my personnel file, and then he sent me to the S-4. The S-4 gave me a Ruck Sack full of ammo for two different weapons, an M-16 rifle and a Russian AK-47 rifle, a compass, canteens, and two pairs of tiger-striped uniforms to wear on missions. The S-4 then took me to the far north end of the camp, where a helicopter was waiting to fly me to the forward launch site. The forward launch site was a location near where the missions were conducted. The S-4 took my bags and said I wouldn’t need anything in them until I came back to Ho Ngoc Tau. I hadn’t been in camp for two hours, and I was on my way to the war. My head was really spinning now. While I was at B-56, each person told me their name, but everything was going so fast I didn’t remember any of them. However, I did see someone I knew from the Weapons course at Fort Bragg; it was Roy Benavidez. Roy had put on some weight since I last saw him two months earlier at Fort Bragg. I asked Roy if he was running Recon. He said no, he was working for the S-3 in Operations. I told Roy I was flying to the forward launch site to be assigned to the Recon Company. Roy said he would see me in two days because he was being reassigned from the S-3 at Ho Ngoc Tau to work for the S-3 at the launch site.

SSG Roy Benavidez

I got on the helicopter, and we flew west for an hour before landing at Loc Ninh. After the helicopter crew shut down the aircraft, one of the crewmembers took me to the TOC , located not far from the helicopter-landing pad. The TOC was inside a large tent with several people running around taking care of business. A sergeant first class introduced himself. He said his name was Ray Stipsky, and he was the first sergeant for the Recon Company. Ray was a soft-spoken man about five feet ten inches tall, very muscular, and appeared to be about

forty years old. Ray said the TOC was talking to a Recon Team on the radio; the team was in enemy contact and had several causalities. Ray said he was trying to get a rescue team together. Ray told me to get my stuff ready to go in with the first helicopter.

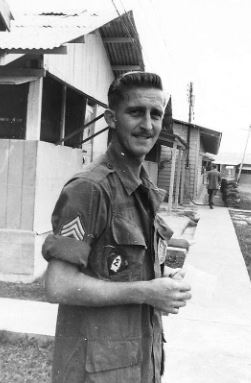

SFC Ray Stipsky

In the next few minutes, I found out there were four teams at the site, and they were all on the ground

conducting reconnaissance (Recon) missions. Sergeant First Class Stipsky, two Como sergeants working

in the TOC, nine Cambodian soldiers left behind from the Cambodian Company, and I were all that could

be rounded up for that rescue mission. There were three UH-1H transportation helicopters and two UH-1C Gunship helicopters left at the site that were ready to go on the mission. The five aircraft crews and the thirteen of us met at the TOC for a briefing. We were told that one of our six-man Recon Teams was in contact with at least a company-size element of NVA (150 soldiers). We were also told to expect more than just a company of NVA in that area. The Forward Air Controller (FAC) was in the area flying over the team, talking to

them on the radio.

The FAC is a U.S. Air Force pilot flying a small two-place airplane called an L-19 Bird Dog. Those airplanes provided the low-speed maneuverability and long endurance required to locate and maintain visual contact with Recon Teams and targets from the air. While in the briefing, I could hear the FAC relaying information from the Recon Team. The FAC said the team had broken contact and was evading the enemy and moving to a Landing Zone (LZ) the FAC had located for the team. The FAC instructed the TOC to launch the aircraft to extract the team. I was told along with the other twelve men that we would stand-down for the rescue mission but would be on standby until the team was recovered. The helicopters would be going on the mission to extract the team.

It was almost dark, and I was thinking, “How are the helicopters going to find the team in the middle of the jungle?” Before I could say what I was thinking, Ray told me that I was going to be a “bellyman” on one of the helicopters. I said, “Okay, what is a bellyman?” A bellyman is a Special Forces soldier who rides behind the pilots in the Huey cargo bay. When the helicopter arrived at the LZ but couldn’t land because of tall grass or trees, the helicopter hovers over the team, and the bellyman throws out three ropes tied to the helicopter’s floor. The team members hang onto the rope, and the aircraft pulls the team out of the jungle on the ropes, sometimes called “the strings” or “the McGuire Rig.”

Bellyman

Because the helicopter is hovering over the team, the pilots cannot see the team, so the bellyman has

to lie on his belly looking over the side of the helicopter, and he gives instructions to the pilot where to

move the aircraft to stay over the team until the team can get on the McGuire Rig. The rig was a 120-foot

rope with a six-foot loop at the end and a padded canvas seat. You rode it just like a playground swing

seat. A Huey could carry four McGuire Rigs, two on each side, but they only use three. The fourth was a

backup. Once the team is on the strings, the bellyman tells the pilot to rise vertically high enough so the

men on the rig clear the jungle canopy, then the helicopter moves forward with the team hanging 120 feet

below the helicopter. In addition, all this is going to be in total darkness. I had no idea what I would do

when I got there, and I knew I would have the lives of three men in my hands hanging below a helicopter.

I received a fast course on how to use the McGuire Rig, and then we were on our way to extract the

team. We flew east into Cambodia, where the FAC contacted my helicopter pilot to guide us into the LZ.

I was in the back of the aircraft along with the door gunner and crew chief for the thirty-minute flight to

the team. I had a headset on so I could hear the radio transmission from the FAC. After thirty minutes, I

listened to the FAC giving instructions to my pilot, telling him what heading to fly to find the LZ. The

FAC guided us right to the LZ, and the pilot made a landing approach straight into the LZ. We didn’t

have to use the McGuire Rig. We were able to see the flashlights of the team on the ground. As soon as

we landed, I saw three men approaching the helicopter’s left side carrying three wounded men. I jumped

out and helped everyone onto the helicopter. Simultaneously, the door gunner on the right side of the

aircraft opened up with his M-60 machinegun.

He was screaming that we were receiving fire from the tree line to our right. The other Huey and

two Gunships were flying above us, and when they heard we were receiving fire, the two gunships started

firing into the treeline to our right. All I could see was a wall of tracer bullets coming down like hot rain.

With everyone on board, we departed under a hail of bullets. We got airborne, and the crew chief turned on the light inside the cabin to look after the wounded men. All three wounded men were in stable condition for what they had been through that day. Neither of the two Special Forces men were wounded, but three of the

Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) soldiers had gunshot wounds to their arms and shoulders. One had lost a lot of blood, and I helped the crew chief stop the bleeding on that soldier.

SFC Don Perry

We arrived at the launch site around 2100 hours, and we were met by medical personnel. I was totally exhausted and still shaking when I went back to the TOC for the debriefing, and that was when I first noticed I had blood all over me.

After the debriefing ended around 2130 hours, Ray introduced me to my Recon Team. The team leader or the One-Zero SFC Perry, his One-One or assistant team leader SFC Cottingham, and three CIDG soldiers. A few minutes later, we were briefed on the next day’s mission, and we would be inserted at an LZ that the SFC Perry had looked at earlier that day. I hadn’t been at SIGMA for 24 hours, and I was going on my first recon mission.

Sergeant First Class Stipsky told me to find a place to put my stuff and get some sleep. I went to a tent

and found an empty cot to rest my tired and scared body. I do not remember how long it took me to fall

asleep, but it was not long.

SFC Jerry Cottingham

I will never forget my first night at SIGMA, and that was just the beginning.

You can Google my friend Roy Benavidez and read what he did just four days after our meeting.