On March 1969 the USMC launched Operation Dewey Canyon. CCN ended up inserting Co A and Co B on top of a Recon Team, with (I think) about two more Recon Teams inserted. I was sent out, with another Cpt, to be the Liaison Officer to the 9th Marine Regiment on a hilltop, near the Ashau, called Fire Base Cunningham. It had a battery of 155mm and about a Battalion of Marines. The other Cpt and I maintained constant radio contact and acted as radio relay to MLT-2 – while our location was being frequently plastered by 122mm artillery fire. The CCN mission was to protect the flank of the 3rd MAR DIV. An NVA regiment closed in and surrounded the CCN forces. Maj Moore, the S-2, was inserted as the Task Force commander. They started a breakout attempt, to walk back to friendly lines, with a Recon Team on point … it was wiped out. There was some pretty heavy fighting. During one fight, Cpt Gary Jones was on the radio with me when he said “I am Whiskey India Alpha!!” Then, he continued on with the operation and was later extracted, but not killed. By the way, SOG also inserted a platoon from OP34 up at Monkey Mountain, commanded by Dick Meadows, off on the (I think Northern) flank to pull the NVA away from our two companies. Dick and his folks then walked out and linked up with a USMC unit at some hilltop, which then marched overland to another USMC firebase for extraction.

We finally extracted the whole operation. With a company being inserted on a ridge line across the valley from our location at Firebase Cunningham. We were socked in most of the time (for about 2 weeks) and they were out of food. I managed to get the USMC to donate some C Rations and had them flown over to our company across the valley, during one of the rare breaks in the clouds. Finally, the weather broke enough to get us all out of the area – still under 122mm fire.

(Filed by Col. Randy Givens).

The support of USMC Operation Dewey Canyon went this way: Jack Deckard was the MLT commander at Quang Tri. Because of the close coordination required with the USMC, Jack Isler decided to go to the MLT, and took me as his CCN Ops officer to the site. Moore went in with the 2 companies, commanding the ground unit, and Gary Jones was his XO. The 2 companies, referred to here after as “Battalion or bn,” got spooked by NVA making noises that had unearthly connotations to the Bhuddist and animistic troops. The Americans were not able to get the troops moving in spite of Jack Isler’s prodding to Moore. The battalion was in danger of being surrounded by the NVA. Isler saw Dick Meadows training a recon team from CCS, for insert into a target the next day. Isler talked to Meadows, and re-prioritized his mission. Meadows and his team were to be inserted to the south of the Battalion, to create diversions to convince the NVA that we had inserted a large force to relieve the Battalion. I coordinated with the Marine Regt in our sector, regarding the insert of this team, and that upon accomplishment of the mission, the team, under command of Meadows, would cross friendly lines in their sector. I briefed and assigned 3 of our CCN officers, including Randy Givens to the Marine units on line. This was done to insure a smooth reentry of the Meadows team. USMC had a strong distrust of indigenous troops. Meadows diversion had the desired effect, and some immediate pressure was taken off the battalion.

Moore called in that he had taken casualties including an American. We ginned up a medevac, loaded extra water, rations and ammo aboard. The medevac got into the site, under fire. When the slick RTB’d, Moore and Gary Jones got off the slick. I asked where the wounded were. Jones had a bandage above his left eye, and he said he was the one. The battalion was left under the command of a young LT, can’t recall his name at this time. I never saw Jack Isler so angry. (NOTE: Both were ultimately relieved and reassigned out of CCN.) Meadows unit reentered USMC lines due to the EXCELLENT coordination by the LNOs with the forward units of the USMC.

While this was under way, GEN Richard Stillwell, CG XXIV Corps choppered in to MLT 2. He was briefed and then told his aide to get CH 47s up to assist with the extraction of the Bn. When the CH 47s arrived, we briefed the crews, and the CWO who was lead, info med us he could not fly the CH 47s into Laos under any circumstance. He was correct, but GEN Stillwell then had his aide call the Marine Air Group Cdr, to send CH 46s to do the job. Short version, they did, took several hits while extracting the bn, and a couple of US and indigenous were wounded. They brought them back to a hill top in SVN. The CH 47s then airlifted them back to a more secure location.

[filed by Maj William ‘Bill” Shelton]

Marine UH-1Es at Fire Base Cunningham during Operation Dewey Canyon

DEWEY CANYON, 1969-PRAIRIE FIRE!

PRAIRIE FIRE

A few days ago I was playing around on the computer and I stumbled onto Tom Hunter’s SPECIALOPERATIONS.COM web site. In Robert Noe’s MAC-SOG section I found a story submitted by Randy Givens and Bill Shelton titled Operation Dewey Canyon, 1969. That story resurrected memories that I have long suppressed. Today is the 15th of March 2000. Thirty-one years ago yesterday, about a mile east of Cunningham fire support base, I climbed onto a UH-1 and eighteen days of gut wrenching, abject terror and debilitation came to an end. This is what I remember about those eighteen days and more. Forgive me if I make a few mistakes on names or some other details, after all, it was thirty-one years ago. There’s an old cliché that goes “Sometimes you get the bear, and sometimes the bear gets you”. This is one that the bear won.

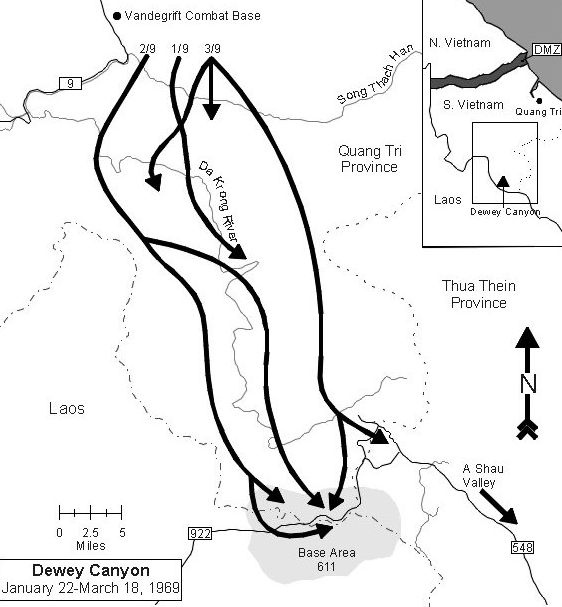

Dewey Canyon was an operation in Vietnam that involved at least a Division of Marines, which took place in February and March 1969. I think the mission was to destroy all NVA forces between Khe Sanh and the Ashau Valley. This is not to be confused with the much more publicized Dewey Canyon II which took place in 1971. In that operation a South Vietnamese Corps, heavily supported by U.S. forces attacked into Laos west of Khe Sanh and had their ass handed to them.

At the time I was a 1st Lieutenant and platoon leader of 1st platoon, A Co (Hatchet Force), CCN, Captain Michael Miller, Commanding. Actually, the term Hatchet Force had been changed to Exploitation Force by that time. As part of the reorganization of MACV-SOG’s OP 35 into CCN, CCC, and CCS in January 1969, word came down that the term Hatchet Force was politically incorrect, thus the change in name. MACV-SOG was an organization that conducted covert operations in Southeast Asia. The largest element of SOG was OP-35’ which consisted of Command and Control North (CCN) in Danang, Command and Control Central in Kontum, and Command and Control South in Ban Me Thout. US Army Special Forces volunteers who led indigenous forces, primarily Nungs, and Montagnards, manned OP-35. The primary mission of OP-35 was to conduct cross border reconnaissance in Laos code named Prairie Fire, and Cambodia code named Salem House.

On February 21st I was alerted for a Prairie Fire mission in support of Dewey Canyon. The next three days were hectic. The mission kept changing, initially a primary mission, then backup, and again primary. First just a platoon, then two platoons, then a company. Then there was the preparation, the briefings, planning, checking equipment, supplies and preparation of packaged resupplies. Fortunately I had a great platoon sergeant, SFC Ralf Hawkins. He was a hardened and savvy combat veteran, a black man, lean and muscular, hard as nails and highly efficient. Every time I see a Lou Gosset movie, I think of him. He’s the one who got the platoon ready while I went through the endless briefings and changes. Even the location for the mission changed. Initially the target area was in Laos south of Khe Sanh where the Laotian border makes a sharp bend back to the northeast in the shape of a fishhook. I forget the alphanumeric target designator, but I did get to make an aerial recon of the target. I went up with covey in the little push-me pull-me job that I think was called an OV-1. I managed to find a primary and alternate landing zone (LZ), and puked a couple of times, all for naught. When we finally launched, the target had changed to Ashau-4 (AS-4), some 25 miles south of there.

On February 24th we moved two platoons lock stock and barrel to MLT-2 (Mobile Launch Team) at Quang Tri. On the 25th it was decided that the mission would be a reconnaissance in force with Company A and a Recon Team (RT). The morning was filled with briefings at echelons above God. There were at least two Marine Corps generals in attendance and if I remember right, neither of them thought much about CCN, and especially our indigenous forces. My platoon had 35 men. Only six of us were Americans, SFC Hawkins, three squad leaders, a medic and myself. The rest of the platoon was Nung (Vietnamese of Chinese ancestry, and good fighters).

The target area was, as I said before, AS-4. About 30 kilometers south of the fish hook, the Laotian border takes a sharp turn straight to the east for ten or fifteen kilometers and then south again along the Ashau Valley. The center of the target box was about halfway east along that turn and south into Laos about 6 kilometers. A high mountain ridge paralleled the border running from west to east and ending precipitously at the northern end of the Ashau Valley. We were to go in on the south side of that mountain ridge, move north across the ridge and toward the South Vietnamese border. The Marines had established fire support base Cunningham, about five or six klicks (kilometers) inside Vietnam, north of the Laotian border. AS-4 was within range of their 155mm guns and they would be our primary artillery fire support.

Weather was lousy, but there appeared to be a break and we launched at 1400 hours on the 25th of February on Ch-34 Kingbees. Here I must digress a little to clear up a few things. If I were telling you about this strictly from memory, I would have said we launched in UH-1’s, however, I know that my memory is fallible so I rummaged around some stuff I’ve kept all these years and found a carbon copy of an after action report that I wrote in 1969. It is clear from the report that we inserted on Kingbees, and many of the dates and such in this account come from that report.

There was only enough lift for my platoon. The rest of the company would have to come in on subsequent lifts. We headed for the target area and, sure enough, things turned to shit real quick. The weather closed in and we had to divert to Phu Bai for refueling and then another try. This time the clouds broke, the sun came out and the verdant jungle mountains of the Ashau Valley and Laos, vibrant with color, spread out beneath us. It was absolutely beautiful and so hard for me to comprehend all the death and destruction that had transpired in that lush landscape. This was my first time “over the fence”, as cross border operations were commonly referred to, and as we crossed the Ashau and closed on the Laotian border my pucker factor went sky high and I forgot the majestic panorama.

We were high, probably even out of range for 35mm anti-aircraft fire, but as we crossed the border that changed. We started a rapid descent toward the LZ, which by the way, had been selected by map reconnaissance by the S-3 (operations officer), and we were soon racing through the sky not far above the triple canopy. At this point I couldn’t have told you where I was or whether we were anywhere near the designated LZ, nor do I think the pilots knew. Suddenly, we banked hard right and headed for an area along the slope that was a paler shade of green than the surrounding forest. It looked to be two or three hundred meters wide and maybe five hundred meters long running uphill south to north. About the time I decided it was an open field I heard three or four crack-pop sounds. I thought it might be the rotor blades changing pitch, but was told later that we were taking small arms fire. I was also wrong about the open field. As we descended the shimmering pale green of the field started to undulate like the ocean sea. We were descending into a growth of young bamboo maybe ten to 15 feet high.

Abruptly the H-34 came to a hover and the pilot signaled for us to get out. I looked down to the ground about 12 feet below me and shook my head signaling him to go lower. He just shook his head no and pointed us out the door again. I wasn’t about to jump, with all my gear I probably weighed close to two hundred-fifty pounds; I would have broken every bone in my body. As it was there was only one thing to do, I turned over on my belly and eased myself out the door thinking to hang below the chopper and reduce my drop to about six feet. There ain’t no skid on an H-34 though, and as my belly cleared the edge of the door, with my M-16 in one hand and my other scrabbling for some kind of finger hold, gravity took over and I hurtled to the ground to land on my left thigh with an unceremonious thud. The rest of the men on my lift followed my example and we were all soon deposited in a heap. The rest of the insertion went the same way; only the platoon got separated into three different areas that might as well have been miles apart for all I knew.

Miraculously only one SCU (an acronym pronounced “Sioux” for special commando unit that we called our indigenous soldiers) broke a leg and the H-34 he was on waited around long enough for the men to trample down the bamboo so the helicopter could get lower and take him back out. Some of the H-34’s had taken more fire than others and one turned back with one of my squad leaders and five SCU. It seemed like it took hours, but it probably only took about 15 minutes for the platoon to find each other and consolidate. My platoon now numbered 28 men, having lost the 6 on the chopper that turned back and the SCU with the broken leg. It was ominously quiet, we couldn’t see ten feet in front of us for the bamboo, and the sun was shining. I felt exhilarated, young and dumb as I was. Sure, we had taken fire, but the rest of the company was on the way and I felt like we could lick the world. We were “over the fence”.

Things took a shitty turn real quick. Covey had been in the area for our insertion and was still on station. Before I could even deploy the platoon to secure an LZ for the company, let alone cut, break or trample the young bamboo, Covey called with bad news. The weather had closed in again between us and the MLT and the returning H-34’s had been diverted (probably to Khe Sanh). The rest of the company would not be coming that day and I was to continue the mission. I wasn’t sure what that meant, whether to continue making and securing an LZ or to do something. I finally decided that we should proceed with the recon in force. I put my best squad on point; I think the squad leader’s name was SSG Charles Gray. SGT Lee was our medic and I put him in charge of what there was of the squad that had lost the squad leader and 5 SCU. They were second in line of march, and the third squad brought up the rear. I followed the first squad with my radio operator and interpreter and SFC Hawkins was behind the second squad. We began moving north, up the mountain in a platoon column. Flank security was impossible because we had to hack and trample our way through the young bamboo that was so thick you couldn’t see a man ten feet away.

As we moved, the vegetation began to change. Every now and then we would break into a grassy open area that afforded us a view of the world around us. What a view it was. To our north about 1000 meters was the top of the mountain ridge looming dark green, almost black, on the horizon. To the west about one or two klicks along the ridgeline a limestone escarpment shining almost pure white in the sun reached up, probably a hundred feet, to a plateau that ran to the west. It looked like an impregnable citadel jutting into a bright blue sky.

Soon we were in a more mature bamboo growth with some other small trees scattered throughout. It was here that the point alerted. I moved forward. The point man had heard voices and movement to our front. Cautiously we continued to move, this time I was at the front with only two SCU in front of me. It was a foolish thing for me to do, as I would soon find out.

The bamboo retreated and we were moving in young relatively open forest and the terrain leveled off somewhat to a bench like area. The farther uphill we moved the larger the trees became, and then there was a deep gully on our left and a path that went north up the mountain along the gully. Another stupid blunder, we followed the path.

We had been moving for about an hour, and it had been at least thirty minutes since the point had alerted. The adrenalin had ceased flowing and my mind started to wander. The vegetation opened up and the opposite wooded ridgeline about 50 to 75 meters across the gully came into full view. I was in the open with just some scattered smaller tees along the path. I was thinking how much this spot looked like a place I vaguely remembered as a child.

The noise! An ungodly roar. Falling. A little tree to my left. My finger repeatedly pulling the trigger of my rifle. My face slamming into the ground. Stuff falling on me, little stuff. Leaves, bark, stuff. Nausea, my bowels feeling like they were filled with water. Every nerve shrinking, every pore tingling in anticipation of objects penetrating, violating. I’m on my belly, I’m turned around, I’m slithering along the forest floor like a black racer. And then, there is Hawkins, above me, yelling at me. What is he saying? “Lieutenant, are you all right?” I am convinced that there are no words in human dialect that can describe such consuming all encompassing fear.

I had led us into an ambush. The clearing along the path was about 50 meters long. It was the kill zone of the ambush and I had been right in the middle of it when the NVA opened fire. Now I was huddled beside the reassuring mass of SFC Hawkins, not knowing what to think or what to do. I think I finally answered his query with a nod, but now, paralyzed by fear, I really had no idea whether I had been hit or not. I hadn’t. God really looks out for fools. The roar had by now become recognizable gunfire. The firing had slowed but some AK-47’s were still firing on automatic, others on semi. Their sharp clatter was joined by the deeper staccato of at least one RPD machine gun. These sounds will be instantly recognizable to me to my dying day. The two SCU who had been in front of me had vanished. Behind me the terrain fell off to the east, away from the gully, so only about two of my men up by me could return any fire, and they were doing that.

I might not have known what to do, or even been capable of doing anything at that point, but Hawkins did. He shouted above the roaring to get an M-79 grenade launcher up front, and then directed the gunner to fire two rounds into the offending noise across the gully. As soon as the first one exploded he had the platoon up and making a beeline back down the ridge to that wooded bench we had crossed about 150 meters to the rear. Of course, I instantly overcame my paralysis and joined him in the dash back down the mountain. Within minutes Hawkins had a defensive perimeter established. I still can’t believe how calm he was.

Hawkins came over to where I was trying to make myself very small behind a large tree and told me we had to get some artillery in quick. I had now regained enough composure to comply when I suddenly remembered the two SCU who had been in front of me. They were still up there somewhere. Then I did something that just added to the list of stupid things I’d been doing. My place was with the platoon and to be in a position to bring whatever assistance to us that I could through our fragile communications link to the world. Instead I told Hawkins to wait on the artillery because I was going back up after those two men. It certainly wasn’t courage that drove me to do that; rather it was pure unadulterated guilt. I had taken them into that ambush and then I had abandoned them.

SSG Gray had been maintaining contact with the point with squad radios. I think they were PRC-8’s, curved rectangular black boxes about 15 inches long that resembled oversized telephone handsets. They had strictly line of sight range, if you were near sighted, so we had lost radio contact as soon as we came back down the mountain. I think I told Hawkins to wait 15 minutes and if I wasn’t back to call in the artillery.

I remembered I had been firing my rifle and thought I had fired most of the rounds in the magazine, so I changed it for a full one. Later when I reloaded the magazine, I discovered I had only fired five rounds. Remarkable when you consider that in the milliseconds it had taken me to fall from an erect dream world that I had been in to my face smashing into the earth, I had somehow moved the selector switch on my rifle from safe to semiautomatic and squeezed the trigger five times. Then I took Gray’s squad radio and my interpreter and started back toward the ambush location. Every few seconds my interpreter would try to contact the missing men on the radio as we cautiously crawled and crept forward. Gut wrenching fear gripped me but I forced myself on. About half way back to the ambush site my interpreter made contact with the missing men on the radio. Seconds later two furtive figures came at us through the brush. It was them, and we were soon back in the perimeter.

My call for artillery was another fiasco. When we had been inserted we had no radio contact with Cunningham fire support base because the mountain ridge blocked our line of sight. Covey had been our only link to friendly forces, but covey was no longer on station. Fortunately we were now close enough to the top of the ridge and we were able established contact directly with the artillery.

Covey had given me a fix (map coordinate location) at our LZ, but I now had no certainty of our location. Dozens of fingers came south off that mountain ridge and we could have been on any one of three or four of them. To be safe I decided to adjust fire by calling for artillery at a set of map coordinates that I knew we were not at, and them adjust from a gun target line. In other words, if I asked for them to adjust right or left it would be from the direction the 155 guns were pointed in. I chose the initial coordinates on top of the mountain ridge, which was still about 300 or 400 meters north of us.

When the first shell came in, if I hadn’t been so scarred as I was at that point, I would have been embarrassed. It exploded so far away from us to the northeast that we could barely hear it. Awkwardly, I called in a new set of coordinates about a klick to the west. That shell also exploded far off, this time to the northwest, but close enough to adjust on. I think I called for them to adjust over 200 and left 200, then held my breath and prayed that I hadn’t called it in on my platoon. The shell exploded about 300 meters to the northwest, at least 150 meters beyond the ambush site, but I figured that was good enough and called fire for effect. The NVA, I am sure were long gone from the ambush site so one place was as good as another. I’m sure that we killed a lot of trees with that fire mission, so when the marine artillery called back for target results I told them they were right on target and broke up an NVA platoon size formation.

II

It was getting late in the day and would soon be dark. We were in a good defendable position, but still far enough south of the ridge where our communication with Cunningham was weak. Hawkins and I decided to try for the ridge top to RON (remain overnight). We moved out in the same formation as before, only this time with me in the right position, and worked our way to the top. This time we gave the path along the gully a wide berth to the east.

As we crested the ridge an entirely different landscape lay before us. It was an area of gigantic trees that rose a hundred feet and more to a thick canopy that blocked out nearly all light. Some of those trees were six feet in diameter or more. Huge monolithic boulders were scattered about like some titan had dropped them on the ground haphazardly. There was little vegetation on the forest floor because the sunlight couldn’t penetrate. The mountain ridge was quite flat and 200 or 300 meters wide in most places. Trails crisscrossed the area and one very well worn path went west to east through the middle. It was obvious that lots of people had been going back and forth in that area.

Hawkins located a good position and got the platoon into a defensive perimeter just as it got completely dark. It was time to take stock. We had been shaken by the ambush, but we had no casualties. We had good communications and plenty of ammunition. We were getting low on water as we had found none to replenish our canteens and most would be out by morning. I was queasy about that well used trail. It was obvious that there were a lot more NVA in the area than there were of us, but the rest of the company would join us in the morning, I thought, so we would be alright.

We also had the Blackbird on station. That was a very specially equipped C-130 aircraft that over flew the trackless, jungle mountains of Laos almost continuously, maintaining communications with various forces, including us, that our national political establishment denied being there. Their call sign was Hillsborough during the day and Moonbeam at night. Moonbeam was sure reassuring that night and even kicked out an aerial flare now and then when we heard, or thought we heard movement around us. Although the flares didn’t pinpoint our location to the NVA, it surely gave them the general area. Not that it mattered, after that late afternoon ambush; the NVA had a pretty good idea where we were anyway. I did not sleep that night.

As dawn approached on the 26th of February, stand-to came and went. Stand-to is when you get everybody ready just before first light, when the enemy horde is most likely to attack. Light came slowly because of a heavy overcast and we were under those giant trees, which didn’t let very much light in anyway. Soon water started to drip on us from that closed canopy. It was raining somewhere up there, but the trees were as reluctant to let the rain in as the light. That didn’t make me feel very good because it dimmed the chances of a quick link up with the rest of the company. My fears were soon confirmed when I got a call from Cunningham. A liaison officer from MLT-2 had been sent to Cunningham to provide a link between the CCN command group and operational forces on the ground. He informed me that the weather still precluded a launch of the rest of the company from MLT-2. I think he passed on instructions for us to remain in place in the hope that the company would be able to launch later in the day.

Late that morning the NVA found us. The squad leader on the northeast portion of the perimeter reported movement and voices to his front. I braced for all hell to break loose, but nothing happened. A deadly game was being played out. I got my interpreter over there because the squad could hear the enemy talking. Two or three enemy soldiers had approached the perimeter and stopped just out of sight and were talking to each other. What they were saying was that the Americans were nearby and that they had better get out of there before they got caught, then they blundered back to the northeast making quite a racket. Obviously they wanted us to come after them. When we didn’t move, some time went by and then they came back and tried it again. Their boldness unnerved me. Somewhere to the northeast was a well-prepared ambush, and there must have been a large force to directly challenge us like that.

Some time after noon we got word that there was no chance for the rest of the company to come in that day. We were to continue the mission. I’d figured out by now that that meant do something. I wasn’t about to lead the platoon to the northeast, so after talking things over with Hawkins, we decided to go west until we found a promising finger dropping off the mountain to the north.

We moved out as quietly as possible, working our way west along the northern rim of the ridge and continuously watching our back trail. I think we tried to move down a finger to the north but it ended abruptly, dropping precipitously into dense forest below, so we had to backtrack and try again. Two or three hundred meters to the west we finally found a finger that seemed to go where we wanted to go. As we moved down the finger, the diameter of the trees got smaller, but it was still relatively open under the forest canopy.

I think everyone was out of water by then. It was still overcast and drizzling, but we were starting to get dehydrated. When we would find a small copse of bamboo now and then we would cut small pieces and chew on it. I provided some moisture and a little relief for our thirst.

Late in the afternoon the finger we were on petered out. I could see quite a ways through the forest. To our left was a deep gorge. Across the gorge, about 150 meters was a high broad ridge that ran down to the northwest. That’s probably the ridge we should have been on. The forest dropped off to our right and than rose again somewhere in the distance, but there the vegetation was much thicker triple canopy jungle and you couldn’t see very far. In front of us the finger we were on dropped sharply down. Far below we could see a swift rivulet running into the gorge to our left. On the other side of the stream was a low finger coming from the east and ending in the gorge. Over that finger another finger rose to the north.

Finally there was water. I was vaguely nervous about how exposed we were to the ridge to our west, but we had to have water and the column was soon slipping and sliding down to the stream to our front. I passed instructions for everyone to stay in a column formation and for each man to fill his canteen as he crossed the stream and continue moving. We would cross the finger on the other side of the stream and then move up the next finger to the north.

The stream was about three feet wide with fast clear water running over a rocky bottom. As I crossed I filled my canteen, dropped in a couple of iodine tablets, and shook up the canteen as I continued over the finger on the other side. Getting water for everyone slowed us down. I was still behind the first squad, and the platoon was strung out at least a hundred meters. I was at least 75 meters up the finger that rose to the north when the last squad was crossing the stream. That’s when the NVA hit us.

The thunderous roar of automatic weapons was deafening. I recognized AK-47’s, lots of them, and RPDs. Added to the din were the sharp cracking of our M-16’s returning fire and the deeper punctuation of our M-60 machine gun and the thump of our M-79 grenade launchers. A new sound to me was the explosions of incoming B-40 rockets as they spattered against the trees around us, filling the air with thousands of tiny metal shards. The NVA were on the high ridge about 200 meters to our southwest, and they had us in the open. Tree bark was flying everywhere and leaves were falling with other debris.

I couldn’t move. I couldn’t think. I didn’t know what to do. But, Hawkins did. He was running up toward me and as he neared he was yelling above the din to get the hell up the ridge, get out of this killing zone. He planted himself about 15 feet below me and to the side, and was urging everyone past him and up the ridge. That’s when I saw the flashes of light seeking the ground around him. Machine gun tracer ammunition what drawing a figure eight around his feet. I screamed at him to move but he ignored the fire and motioned me up the ridge yelling at me to get up front and find a place we could defend. I watched him for a few moments, in awe at his calm as the ground was torn up around him, and then I was running.

It was steep, but I ran harder than I’ve ever run. Unbelievable fear, but this time, no panic. I had to get to the front of the fleeing column and get the platoon under control. About 200 meters up the finger I caught SSG Gray with the first squad. At that point the finger joined a broad ridge coming down from the southeast. It dropped sharply to the north, but was relatively level to the east. I couldn’t breath, I couldn’t talk I was so winded, so I signaled Gray to the east and we ran on. Abruptly the forest ended and we were in an open field.

I was in a field of waist high grass, which dropped steeply downhill to the north. The field was about 250 meter wide and tall dense forest lined its eastern edge. It dropped downhill about 400 meters to a huge cone shaped hill mass that I could barely make out in the misty overcast and drizzle. Uphill to my right about 100 meters the hill seemed to level out in an area of scattered trees. Right where the field started to level off I saw a dark opening on a small mound. My stomach almost came up in my throat as I realized I was looking into the mouth of a bunker. There was no firing from that direction though, only the firing down behind me which was rapidly tapering off. The bunker area was either unoccupied or the NVA were waiting for more of us to get in the open.

I had no choice; we had to move up to the bunker area. It was the only defendable area I could see. I broke right and signaled the platoon up the edge of the wood line to the bunker. The NVA were not there. Above the bunker the forest closed in on the sides and the terrain leveled off somewhat in a relatively open area about 100 meters wide and 100 meters deep. It wasn’t ideal, but the terrain dropped off into the forest on the east and west sides, and rose gently through the forest to the south. To the north the open field dropped steeply in front of the old bunker. It would do.

It was getting dark fast, especially in the drizzling overcast. Hawkins brought up the rear and herded the exhausted platoon into the perimeter. It was time to take stock. SGT Lee, our medic who was standing in as my second squad leader had been hit in the leg. Five SCU had been wounded, three of them seriously. The worst was that one man was missing. He was a Nung, and I knew him. He couldn’t have been over 16 or 17 years old, was a cheerful impish boy with a wide smile and quick laugh. He had been near the end of the column and was filling his canteen in the stream when we were hit. When the great roar of gunfire exploded, he had fallen forward face down in the stream and never moved. His squad members who passed him thought he had been killed instantly.

Leaving that man has haunted me to this day. I couldn’t jeopardize the lives of the entire platoon to go back for a man who was probably dead, but was he? I have often asked myself a very disturbing question. Would I have gone back for him if he had been an American?

The only possible fire support we could get in that weather was the 155mm artillery from Cunningham. We soon had a fire mission going into the gorge where we had been hit by the NVA. If they were trying to follow us they took a plastering.

The liaison at Cunningham was hounding me to give him a sitrep (situation) report. I recognized the voice as that of Major Moore, a senior staff officer from CCN. Trying to get in the artillery, take care of the wounded and get the platoon into a good perimeter seemed more important to me than taking the time to give a sitrep. Besides, I was scarred to death and cold, wet and miserable to boot. Those were the days before we had secure voice radio, so anything of importance had to be encoded from an SOI (a code book), or sent by agreed upon brevity code. At the time the brevity code for Americans, I think, was Straw Hat, and for Indigenous White Hat. In my near panic condition I sent a short message that said we had 1 White Hat WIA, 5 Straw Hat WIA, and 1 Straw Hat MIA. Of course I’d gotten it completely backward and that really caused some consternation.

Major Moore asked if I was sure of my report. I said I was, and then he came back and asked if I was declaring a Prairie Fire. Prairie Fire had a couple of meanings. That was the code name for the area that CCN operated in, that portion of Laos 20 to 30 klicks deep, west of the Vietnamese border and north to where the Ho Chi Minh trail entered Laos from North Vietnam. It also had a more forbidding meaning. If a recon team or hatchet force got into trouble so serious that annihilation was imminent, they declared a Prairie Fire. With that declaration all available firepower, air and ground, within range of the emergency was immediately diverted to their assistance. If a Prairie Fire was called lots of people, good guys and bad guys, were going to die. We had evaded the NVA and were not under immediate attack, so I told him no, and realizing my error, I corrected my sitrep.

I was so miserably frightened by then, very nearly in tears, that I reached blindly for help. I think I said, “Major Moore, what am I going to do?”. There was dead silence for a moment on the radio, and then Major Moore came back with “Calm down son, we will get you a medivac in the morning.” Then he reminded me not to use names on the radio.

I got with Hawkins and we burrowed into a depression behind a big tree on the eastern side of the perimeter for the night. We should not have been together because if one of us was hit, the other could take charge, but I needed him near me then. I wanted to lie beside him and perhaps some of his calm and courage would seep over into my body. It was a long night and I didn’t sleep again.

We were all wet and cold. I’m originally from northern Michigan, but I think I was colder that night than I have ever been. It was absolutely black. It really was rough on the wounded; especially one of the Nung’s who had been shot through the stomach. He had to be in horrible pain, but he never made a sound that night.

During the night we heard clicking noises down in the draw to our northeast. It may have been the NVA signaling to each other while trying to find us, or it may just have been wind blowing through the bamboo. At any rate it kept me on edge. I may not have been able to sleep, but Hawkins did, and loudly. He would start snoring and to me it sounded like a chain saw. I was sure every NVA soldier within a mile could hear him. I kept waking him up, but it did little good as he was soon sawing logs again.

Time for stand-to finally came and we all held our breath awaiting the assault of the enemy horde, but they did not come. They had not found us during the night.

I hoped that we would get our wounded evacuated soon and that the rest of the company would join us. It was not to be. Everything east of us was still socked in. Still, we had to get a landing zone ready for when they could come. We went to work clearing the area within our perimeter. Several small trees were removed using C-4 explosives and we brushed out a reasonable area for a one ship LZ, however far above us a large branch from a giant tree hovered out over our LZ. A UH-1 might be able to come in under it from the north, but it would be tight. Using C-4 on the tree was futile; it had about a five-foot diameter trunk. One of my squad leaders came up with the brilliant idea of blowing off the offending branch with a LAW (light antitank weapon). He tried twice I think, but of course, he missed.

Covey was on station by then and let us know that a CH-46 was on the way to evacuate our wounded. There was no way that a CH-46, a large twin bladed cargo helicopter, could land in our perimeter, and when it arrived, our doubt was confirmed. They were going to have to use a jungle penetrater to extract our wounded. This was a grappling hook like thing that was lowered by cable and the person being taken out would sit on the forks of the hook and hold onto the cable while being winched back into the helicopter. Three of our wounded were serious and would never have been able to hold on while being winched up a hundred feet or more. SGT Lee went out first and held on to the most seriously wounded of the Nungs, the one shot through the belly. Then the two lightly wounded each took another of the more seriously wounded to get the rest out.

While the wounded were being evacuated, one of my squad leaders brought me a note that had been dropped from the helicopter. It was scrawled on a folded piece of paper and it was from Captain Miller. He had written some encouraging words and assured me that he would be coming with the rest of the company as soon as possible. His concern moved me and gave me a little added strength.

Clearing the LZ and getting the wounded out took most of the morning, and I had no doubt that every NVA soldier within ten miles now knew exactly where we were. At this point there were just twenty-one of us left. We had lost a quarter of our strength in the firefight with the NVA the evening before. With no hope of the rest of the company getting in that day, things looked very grim. Attack was imminent; it was just a matter of when.

The sun was out and it was very clear. To our north the mountain dropped off steeply about 500 meters to a large cone shaped hill that rose abruptly above the surrounding forest. Beyond that about three kilometers was the South Vietnamese border. There the jungle yielded to undulating hills stretching north toward Khe Sanh. The colors were vibrant, mostly shades of green from emerald to almost black. Every so often the shades of green were broken by slashes of reddish brown where the earth had been exposed. It was gorgeous. I later found out that the Ninth U.S. Marine Regiment was engaged at that time in a bloody struggle with the NVA. At about that time, two companies of marines were virtually annihilated just on the other side of the border to our north. Dewey Canyon was a costly battle for the marines. I think that that is where the Ninth Marines had the name “The Walking Dead” bestowed on them.

Time went inexorably slowly by as we waited for the NVA to attack. Everyone dug in as well as they could. We didn’t carry any entrenching tools, so the men dug with knives, canteen cups, sticks and bare fingers into the concrete hard unyielding earth. We were also very low on water; most having only gotten one canteen filled in that deadly gorge the day before. Everyone was exhausted, thirsty and scared. Still the NVA did not come.

Darkness came and another uneasy night. This time I slept a little, fitfully, through sheer exhaustion. Again the dawn approached and still no NVA. That soon changed.

As the sun came up on February 28th, Covey came on station. Very soon the radios started humming with communications traffic. Covey had seen something. And then it happened. Covey had declared a Prairie Fire. By listening to Covey reporting the situation to Cunningham I was able to piece together what was happening. There certainly wasn’t any other indication to us, as it was deadly calm and silent around us. Covey had spotted the NVA massing to attack about 300 to 500 meters from our position. He was able to count about 300 NVA to our north and west. I tightened up perceptibly but managed to alert the platoon. Our 21 soldiers huddled in the little holes we had scratched in the earth on that Laotian mountainside were merely an irritating bunch of insects about to be crushed by at least a battalion of NVA. Then the gods of war unleashed their fury on the NVA.

It wasn’t really the gods of war; it was the wrath of the U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Army, and U.S. Air Force that descended on the NVA. For several hours, it seemed, the sky was filled with various aircraft and the deadly ordinance that unmercifully sought out the enemy. Marine 155mm artillery crashed almost continuously into the mountainside. Army and Marine gunships came and went expending machine gun, cannon fire and rockets into the enemy. A flight of Spads, WWII and Korea vintage propeller driven fighter/bombers, came on station sending cannon fire and bombs into the inferno. They went away and after a while came back and did it again. Then as kind of a finale to the carnage, there was a whine, whoosh, roar directly over our heads as a pair of F-4 Phantom jets came over the top of us flying from east to west. And then they were gone and there was quiet followed momentarily by crashing, roaring, repetitive eruptions rising out of the west and engulfing us. The F-4’s had released their bombs before they were even over us and the bombs had rolled and tumbled over our heads and ferreted out the desperate enemy in the deadly gorge to our west. Then there really was silence.

The NVA attack was shattered. We had not seen an enemy soldier, not had a shot fired at us in anger. Covey had directed the whole show from somewhere up above. I thought about all of the carnage in the void of the deadly gorge to our west and the base of that cone shaped hill to our north, about the hundreds of mutilated, torn, ruptured human beings littering the forest floor somewhere just out of sight. All I did was thank the good Lord above that they were dead and we were alive.

There was no more activity the rest of that day. We remained in a state of high alert, but the response to the Prairie Fire had broken the back of the NVA. Now we only had the elements to contend with. We were now all out of water, and no way to get any. Thirst began to work its debilitating effect on us.

Toward evening the liaison at Cunningham got ahold of me on the radio. The remnants of the NVA that had attacked us had withdrawn north and joined the NVA forces that had been fighting the Marines and then pulled back across the border into Laos. Apparently they were located between the cone shaped hill to our north and the border. There were estimates of up to three regiments of NVA in that area. Shortly after dark there would be an Arc Light in that area, and we were to hunker down and do what we could to protect ourselves. The B-52’s would be making their run from east to west about 1500 meters to our front.

Darkness came, we got the warning that the mission had begun and we burrowed as deeply into our scratched out holes as we could. Then the earth was trembling, shuddering and a long continuous moaning roar enveloped us. It seemed that the earth trembled for a long time and the noise and concussion filled my head as I dug my fingers into the dirt to keep from being extracted from my hole. Then dead silence and blackness of night closed upon us. In spite of my thirst and terror, I slept a little that night

III

With the morning of March 1st came the sun, clear skies, and good news. Help was on the way. The bad weather to the east had lifted and long awaited reinforcements were on the way to link up with us. Not only was Captain Miller with the rest of A Company coming, a whole task force was on the way. A Company was being joined by B Company of the hatchet force, commanded by Captain Gary Jones, and two Recon Teams. In all a couple hundred men would form the task force, and Major Moore had joined them and would be in command.

Task Force Moore was not as strong as it could have been. The rest of A Company consisted of two under strength platoons, which Captain Miller consolidated into one full strength platoon. One of the platoons was commanded by 1LT Phil Bauso and I felt good about him. He was a law school graduate, from the Bronx I think, and shortly after he passed the New York bar examination, he had joined the army and volunteered for Special Forces and Vietnam. He was a hard charger, always volunteering for the most dangerous missions, and he was an outstanding platoon leader. Unfortunately he left on R and R just before the mission and had not yet returned. The other platoon didn’t even have a platoon leader until a day or two before this mission. A heavyset Lieutenant named Willard joined Captain Miller at Quang Tri just in time to accompany Task Force Moore.

Other shortages were to be filled by volunteers. Two of those volunteer who I remember well were Captain Bobby Blatherwick and SGT Sanderfield Jones. Bobby was on a six-month extension of his tour of duty and we had developed a personal friendship. Bobby was a courageous man. Just six months prior to Dewey Canyon, enemy sappers, had attacked CCN at Marble Mountain on the 23rd of August, and 17 Americans had been killed. A great number more Americans and indigenous soldiers had been wounded. Many of the wounded owe their life to Bobby. Somehow he got to a vehicle and throughout that hellacious night he had driven around the compound during the fighting to recover the wounded and get them to medical help. All of the tires on the vehicle had been flattened by enemy fire before it was over. Bobby would come along as an extra officer in the Task Force command group. SGT Jones who was assigned to MLT-2 at Quang Tri volunteered to be one of the consolidated platoon’s squad leaders in A Company. I have always remembered Sanderfield Jones for what would happen in the next few days.

The task force came in on the same LZ that my platoon had been inserted on five days before, and they encountered the same difficulty. The helicopters off loaded the men 10 to 15 feet above the ground because of the high bamboo. LT Willard who had only been with the company a day or two broke his leg and had to be taken back out. That is when Bobby Blatherwick took over the platoon. I can’t remember if anyone else was lost.

We were told to stay put and that the task force would link up with us. Covey was again on station and took on the task of guiding the task force to our location. All we could do was wait. We were in pretty bad shape by then for lack of water. We still had food as each of us had started with five days rations, which meant we carried one meal a day for the five days. What we had though was a mix of long range reconnaissance patrol rations (lrrps) and the Vietnamese equivalent. The lrrps were dehydrated mixtures of hash or such and the Vietnamese rations were a mix of rice and dehydrated shrimp and fish. The problem was that you had to have water to prepare them; so most of us had only eaten one or two meals in the last five days. We were weak and terribly thirsty. My lips were cracked and my tongue felt so swollen that it was difficult to talk on the radio.

Sometime during the day SSG Gray reported that his squad detected movement south of the perimeter. The task force was still a couple klicks away so either it was the NVA or some unseen forest creatures moving nearby. It kept us on edge.

Captain Miller knew what kind of shape we were in and he pushed hard to try to get to us that day. At one point close to dark he was far out in front with just his radio operator and then even the radio operator fell back. Finding himself alone he had to fall back to the task force. About dark the task force made it to the top of the mountain ridge where they established a perimeter. We were still 1000 to 1500 meter to the northeast of them, so we hunkered down for another night.

That night Captain Miller called me on the radio and told we that the platoon would have to move out and link up with the task force in the morning. I did not feel very good about the order because we had heard movement outside the perimeter to the south during the day. That was the direction we would have to move in the morning. I’m not sure why, but I think the order was a result of decisions made on what the task force would be doing after the link up. They did not want to waste any more time coming to us and then backtracking.

Shortly after dawn on March 2nd we cautiously moved out of that position that had been our safe haven for the last three days and nights. Everyone in the platoon was sure that the NVA were waiting for us and responded accordingly. We moved in platoon column, slowly and stealthily. We had flank security out as far as possible, and every man continuously examined every fold in the ground for where he could take cover if we were hit. We had learned from bitter experience how to move in hostile territory and were ready to respond to anything. Covey was again on station and guided us toward the task force. For several hours we worked our way south up to the top of the mountain ridge, and then turned west moving along the ridge toward the task force.

Linking up with friendly forces in hostile territory is a very dangerous task. Frightened men on both sides might mistake the other for enemy forces and be quick to fire. It may have been even more dangerous for us. We were dirty, worn and haggard. We wore olive drab jungle fatigues with no marking at all and floppy boonie hats or just green bandannas tied around the head to keep sweat out of the eyes. The bulk of our force was indigenous and at a distance we were probably indistinguishable from the NVA. Really, that was the idea; the more we looked like the enemy, the greater chance that the enemy might hesitate for a moment if we ran into them. That would give us a slim edge. This time, the link up went very smoothly, primarily because First Sergeant Fisher of B Company came out from the task force perimeter with a radio, all by himself, and talked us in to his position. I was never so happy to see that lean, wiry, professional noncommissioned officer, as I was that day.

We were really done in and completely dehydrated from lack of water, so Captain Miller saw to it that the rest of the company divided what water they had with us. The squad leader and five Nungs that were on the helicopter that turned back when my platoon was inserted on February 25th had come in with the rest of the company and now rejoined us. Now I had 27 men in my platoon. Captain Miller then directed me to put my platoon into the southwest part of the perimeter, but to be careful because he had already lost one of the SCU to a mine. Evidently, a Recon Team had been in this position about a month earlier and had left several mines emplaced. They were toe poppers, M-14 anti-personnel mines I think. They were small, about as big around as a tomato soup can, but only about half as tall, and made out of olive drab plastic. The pressure plate was slightly smaller in circumference, and when they were dug in, they were nearly impossible to detect. They were not designed to kill, only to maim, and they lived up to their name. It wasn’t long before one of my Nung’s stepped on one and shattered his foot. I was terrified, and I’m sure everyone else in the platoon was too, as we moved into our position and began scratching out our fighting positions. Every step I took I cringed with anticipation of the bang and explosion of pain that would announce that I would be crippled for the rest of my life. Needless to say, once we burrowed into our position, nobody moved unless they absolutely had to.

The Task Force had planned to move out as soon as we linked up, but that had changed when the SCU had stepped on the toe popper. Now one of my Nungs was also wounded and we were waiting for a medevac helicopter. The perimeter that we were in was located on the southern edge of the mountain ridge and relatively open. The recon team that had been here about a month before, the same one that planted the mines, had cleared a small landing zone on the southeastern part of the perimeter and they had been extracted from there. This is where the helicopter landed late in the day to evacuate our wounded. By then it was too late to do much so Major Moore decided to RON where we were.

I was happy with that decision because my platoon was exhausted and needed the rest. I broke open one of my rations, a lrrp, broke off a piece of C-4 plastic explosives about the size of the end of my thumb, lit it with a match and soon had a canteen cup of water boiling. The boiling water went into the plastic bag of dehydrated hash, or chili, or whatever, and in a couple minutes it was edible. As darkness approached, Hawkins organized a watch where one third of the platoon would be alert as the rest slept. I curled up in my shallow depression and sweet blackness enveloped me, probably more unconsciousness from exhaustion than sleep.

The wail pierced my brain, jarring me to consciousness. The blackness was filled with noise, screeches, howls, yips, barks, grunts, and unintelligible noises. It took my brain a moment to focus, and then I remembered where I was. The guttural explosion of noise went on, but there was no firing, so I finally decided that we were not under attack, but I could not figure out what the ungodly racket was. The radio was humming by then and Captain Miller was soon querying me as to what the hell was going on. The noise wasn’t far from where I huddled in my little depression. It was coming from my platoons sector, and although it didn’t sound human, it was probably coming from one of my men.

I grabbed my interpreter and radio operator and we scurried toward the source of the clamor through the blackness. About half way to the position I suddenly remembered the mines. My stomach rolled and my sphincter tightened perceptibly, but there was nothing for it but to keep going. The source of noise had to be found out. A huddle of figures appeared out of the blackness. One was Hawkins, he had gotten there already, and the others were Nung. One of them was thrashing and flailing on the ground, and the unintelligible panoply of noise emanated from his writhing body. I chanced a quick look with my red lens covered flashlight. The man’s face was contorted and his eyes had rolled back in his head. It looked like he might have been having an epileptic fit. I demanded the interpreter find out what the hell was going on to no avail. All we could do was hold down the flailing body to keep the man from injuring himself.

It seemed like a long time, but it was probably no more than five minutes, until the man stopped the flailing and noise. There was a huddled whispering in Vietnamese as the Nungs sorted things out and then my interpreter was back with me. It seems that what I had witnessed was a Buddhist version of speaking in tongues. The Nung was a Buddha talker. When the man had regained his composure he told the others that he had talked to Buddha and that Buddha had told him that there were many NVA in the area and that there was going to be more fighting. Now, I could have told them that without talking to Buddha, but to the Nungs, this was a very spiritual happening, and it had a noticeable effect on them.

The Nungs were a peculiar people. They were Vietnamese, but they stubbornly hung on to their Chinese heritage even though they had lived in Vietnam for several generation. They didn’t look unlike the typical Vietnamese, except on the whole they tended to be a little shorter and thinner. They were proud of their ethnic minority status, and they were devoutly Buddhist. After the Buddha talking incident, I had to keep sending my interpreter out to make them put out the Buddha incense sticks that they started. Some Americans did not trust the Nungs, perhaps for good reason. I had Nungs in my platoon who openly expressed sympathy for the North Vietnamese cause, but they decided to fight for us rather than the NVA or the South Vietnamese Army because we paid a hell of a lot better. There was one old Nung in the company who was to old to go on operations so we just used him as a houseboy. He had fought for the French, in France, during World War I. Another Nung in my platoon was about 35 years old. He had fought at Dien Bien Phu, with the other side. The youngest was a 14-year-old boy who wasn’t much bigger than his M-16 rifle. I kept him near me most of the time.

The morning of March 3rd was overcast and dreary. Captain Miller called Bobby Blatherwick and myself to his position to lay out the planned movement of the Task Force, which was to move out shortly. B Company would take the lead in column of platoons and move east along the ridge. My platoon would follow B Company and Bobby’s platoon would bring up the rear. As Captain Miller talked I heard a sharp pop from the direction of my platoon’s position, followed by shouts and a commotion. We all knew immediately that someone had stepped on another toe popper mine. Sure enough, another of my Nungs had been crippled by one of those hidden hideous devices. I was now back down to twenty-five combat effectives in my platoon, including myself, having lost two men to those mines.

Of course this latest circumstance put the Task Force operation on hold as a medevac had to be called for the wounded Nung. Again, the weather was lousy and it was late afternoon before a helicopter finally made it in to evacuate the wounded man. Most of the day had been lost so Major Moore decided that the task force would stay another night where we were and move out first thing in the morning.

I said earlier that my platoon was now down to twenty-five combat effective men. That was problematic. We had now been in Laos for seven days. Fear and adrenaline had kept us on an edge for most of that time, but now we were no longer alone. When we had linked up with the Task Force we had been engulfed in a blanket of security and safety that most of us had all but given up on. The adrenaline was no longer pumping and that left us in a down of near lethargy abetted by physical exhaustion, dehydration and malnourishment. When I think back on it, at that point we really weren’t worth a damn. I would find out in the days to come though that fear is much stronger than debilitation, and that human beings can endure far more than we sometimes think.

Buddha spoke again that night. The message was the same, but the maniacal thrashing and howling of my Buddha talking Nung was no longer a cultural novelty. Captain Miller got me on the radio, chewed my ass out, and told me to get my people under control. Fortunately, Buddha didn’t have a long conversation that night, but I still had to chase the odor of smoldering Buddha sticks until dawn.

We moved out shortly after dawn on the 4th of March. The task force was moving east along the mountain ridge toward the northern end of the Ashau Valley. Movement was slow and cautious. We were a force to contend with now, but every one of us knew that this was the bad guys back yard and that there were still lots more of them than there were of us. Evidence of that fact was apparent. We followed well-worn trails that were sometimes as wide as country roads. B Company soon found a cache of rice, they found several that day. They were probably bags of rice stacked under thatch shelters, but by the time my platoon passed them they were smoldering, black, lumpy piles of unrecognizable fodder that filled my nostrils with the stench of putrid sulfur. B Company had destroyed each cache with white phosphorous grenades.

The flora changed as we moved east. We were soon out of triple canopy rain forest and spent most of the day moving through lower growth forest with frequent open areas of high grass and small trees. Most of the time I was able to keep flank security well out from the main column with intervals of thick brush forcing them back in on the platoon. The weather cleared and a warm afternoon sun brightened an azure sky.

In mid afternoon, the task force came to a point where the mountain ridge split. We had been gradually loosing elevation for a couple of hours, and now one ridgeline to the front dropped off gradually to the east, the way we had been moving, and another forked off to the southeast. Major Moore decided to follow the ridge down to the southeast, why, I don’t know. At that point I was just a platoon leader in a battalion size task force, and not privy to discussions and decisions made at the Task Force level. Undoubtedly, Major Moore was in contact with higher headquarters and was receiving intelligence and direction on what we were supposed to do and where we were supposed to go. At least I hoped so.

About an hour before dark we moved into a perimeter to RON. Bobby’s Platoon and mine closed the back door with my platoon settling in from the center of the ridge south and east to where we tied in with a platoon from B Company, and Bobby securing an arc to the north and east to another B Company platoon. We were in a relatively level area of young forest with most of the trees about ten inches in diameter and not too much brush. I checked each position paying special attention to the placement of the M-60 machine guns to insure that they could provide protective grazing fire across our platoon front. That night we would be on fifty percent alert with one man always awake in each two-man position. Then I broke out my last ration and used the last of my water to prepare it. If I remember right, it was a PIR, the Vietnamese equivalent of a long range patrol ration. I think it was shrimp and mushrooms and of course rice. That was the fifth meal I had eaten in the last eight days. It would be a long time before I would eat again.

Again the black Laotian night was fractured by the wails, shrieks, howls, yips and grunts of Buddha speaking. Captain Miller’s patience was at an end. He called me and told me that if I couldn’t control my people, he would replace me with someone who could. I had just about made up my mind that I was going to cut that son of a bitch’s throat so he could talk to Buddha in person, and I let the Nungs know it. The last eight days had hardened me into a person that I didn’t even know, and I think I really would have done it. I think the Nungs thought so too, because the clamor stopped as suddenly as it had begun. It didn’t take long though, for the word to spread, not only through my platoon, but through the whole task force, that Buddha had passed on a grave and foreboding message. The Buddha talker said that a division of NVA now surrounded us and that the morrow would bring much death and destruction. There were no smoldering Buddha sticks to contend with that night, but I could feel, and smell, the fear that permeated the indigenous troops. Hell, I was scared too.

I don’t know whether Buddha’s visit had anything to do with it or not, but when morning came on March 5th the Task Force’s direction of movement was changed. We reversed course and moved out in the direction that we had come from. One of the two recon teams with the Task Force took the point followed by Bobby’s platoon, then my platoon, and then B Company. We followed our back trail all morning without incident, then, early in the afternoon we found a wide ridge dropping off to the north and started down it.

The weather had cleared and we moved under a bright blue sky. It was warm, but not uncomfortable. It would have been a lazy walk in the sun except that every man was super alert and on a keen edge, knowing in the back of his mind that today he would see the elephant. Then the elephant appeared.

It began with a burst of fire, and confusion. Captain Miller was on the radio trying to contact Bobby to see what was happening, but couldn’t raise him. Bobby’s platoon sergeant, SFC Hall, answered Captain Miller that another cache had been found and that Bobby was probably destroying it. I knew better. That burst of fire had come from an RPD. I recognized that sound now with a certainty. Then up ahead the jungle exploded in the crescendo of a full-fledged firefight. Where I was, the ridge had narrowed somewhat and to my right it dropped off into a small heavily wooded gully. Up ahead I could see that the ridge widened out again and seemed to level off a little. We were in mature forest with relatively thick underbrush. The Nung in front of me suddenly pointed his M-16 into the gully to our right and fired a burst on automatic. There was nothing there. This was the fourteen year old that I kept near me and he had simply fired his weapon out of excitement and because he hadn’t had the opportunity to shoot prior to then. Then everything became a blur, with stark images interspaced that have stayed with me to this day.

Noise! Bobby on the radio. Recon Team ambushed. Noise! Bobby…”I’m flanking right, send Burns left”. Hawkins with me. I shout at him…”Two squads left on line, one follow”. Noise! Crashing through brush. Running. Can’t see my squads. Noise! Movement to my right…it’s Bobby’s people. Running. In the open now. Noise! There’s Bobby. Waving his arms at me, what’s he saying? He has a grenade in his hand. Pointing ahead. Noise! Scattered trees. Open grassy forest floor. Things scattered on the ground. They are bodies. Not moving. Noise! Somewhere to my left shooting..my people. Running. Big tree down about fifty meters ahead. Bobby’s pointing. Noise! He’s pointing at the log up front. Holds up the grenade. I rip at the tape securing the grenade on my left web gear strap. It’s in my hand I yank on the pin. Running. Noise! Bodies on the ground. They our ours. Please don’t shoot our own men!! Noise! A figure to my right. It’s Sandy Jones. Why is he sitting there? Legs sprawled. Arms flailed. Hands on the ground. Palms up. Brownish splotches etched up his right leg…right side…right chest…lip split to his nose. He’s propped against his backpack. Dirty blond hair whisping from under his boonie hat. Staring at me. Left eye wide-open…surprised…right eyelid drooping over half open eye. He doesn’t see me. He doesn’t see anything. A Nung on the ground to my left. Not moving. Head looks funny. Where is it? Half gone. White stuff bulging out…its his brain…no blood. Another shape to my left. It’s Himes. He’s on the recon team. Prone position. Car 15 aimed to the front…finger on the trigger. Why doesn’t he shoot? Why doesn’t he move? He’ll never move again. Running. NO NOISE!! Just ragged breathing..gasping really..mine. A blur on my right. It’s Bobby. We are both falling. Not falling..jumping. My chest hits earth. I slide up to the log. Bobby slides up beside me. I do not throw my grenade.

It was over. I was completely numb, and thirsty. Very, very thirsty, but I had no water. On the other side of the log there lay an NVA pith helmet and an AK-47 assault rifle. There was no other evidence that the enemy had been there. Except for the bodies, ours. I can’t remember exactly how many men were killed and wounded, but Sandy Jones and Earl Himes were dead and some of the SCU. Every man on the recon team was killed or wounded. From Bobby’s platoon Sandy was dead and one of the Nungs in his squad was seriously wounded. Sandy had gone to the sound of the guns. He had led his squad in a headlong charge straight down the ridge. The RPD had stopped him about thirty meters short of the big log. That charge probably saved the lives of those on the Recon Team who survived. Surprisingly, the Nung with his skull blown off would live. He would come back to CCN at Marble Mountain with a flap of skin sewn over his brain and continue to serve on the payroll as a houseboy or some such. That was the way things were, we kept the faith with those who fought with us.

Nobody in my platoon had been hit. I took stock of myself and it wasn’t a pretty sight. Blood was running down my right leg and my trousers had been ripped open from mid-thigh to the cuff. It was not a wound; rather I had ripped open my pants and gouged myself in the leg running through the brush. My platoon had been in Laos now for nine days and I was dirty, unshaven and stank. I’d only had five meals during that time and had suffered from dehydration much of the time. I was loosing weight and it was starting to show. In fact, before this was all over I would drop from 170 pounds to 135. What is important about all of this is that I was not unique. Every man in my platoon, except for the six who had rejoined us when we linked up with the task force, looked and stank just like me. We had now been through three firefights with the NVA, endured a Prairie Fire, had no more food or water and were starting to get short on ammunition. We were not yet combat ineffective, but we were headed in that direction. Still, nobody had given up. They were not giving up now and they would not give up in the ordeals they were destined yet to endure. I was hungry, thirsty, exhausted and scared shitless, but another feeling began to emerge from the recesses of my numb mind….Pride! These men, my men, had, like Sandy Jones, gone to the sound of the guns. They had deployed and advanced into the fire and the enemy had been driven back. It was none of my doing. It was the raw courage and tenacity of those Nungs, my Nungs, and the professional leadership of determined American NCO’s like Hawkins and Gray and Lee and others, who ,God forgive me, I can’t remember their names. These were men, my men, and they were soldiers.

IV

We immediately began to establish a defensive perimeter and prepare an LZ so the dead and wounded could be evacuated. Behind me the terrain was relatively level, slopping gently up the ridge to the south. The eastern side of the ridge was quite open, just a few scattered small trees to bring down to make a good one ship LZ. There it opened up completely to a field of tall grass that dropped steeply to the east. The field was about 150 meters wide and ended abruptly at a heavily wooded ridge, which rose steeply to the east of us. That ridgeline ran north and south and curled up to our position about 150 meters to the south. To the northeast a couple of hundred meters the field dropped over the horizon offering a panoramic view of Vietnam far to the north. If I hadn’t been so scared out of my mind at the time, I may have appreciated the beautiful view. Sometime while we were there, Bobby took some pictures of a sunrise from that spot. I still have two of those prints in a dilapidated old scrapbook. The south portion of our perimeter was heavily wooded and thick with undergrowth. That was the stuff we had just attacked through. To the west the trees were smaller and the forest floor was relatively open, the terrain dropping down to a wooded bowl and rising again somewhere to the west. The log I had ended up at was on the crest of the ridgeline we had come down. The ridge was about 75 meters wide at that point and ran gently down to the north through open forest.

Bobby’s platoon had taken casualties so Captain Miller pulled his platoon back and gave them the western portion of the perimeter. My platoon was given responsibility for the northern portion of the perimeter back around to the LZ. B Company secured the LZ and the southern half of the perimeter. Some people were gathering the casualties and preparing them for evacuation. Others worked at clearing the LZ. I’m sure I remember that the Task Force registered artillery from Cunningham during that time. That is, artillery rounds were called in until one exploded at a point satisfactory to adjust from if a fire mission were needed in a hurry. The rest of us dug in as best we could. The ground was rock hard but after an hour or so I had managed to scratch, claw and dig with a K-Bar knife and my canteen cup, a rifle pit about six or eight inches deep and the length of my body. God I was thirsty.

A CH-46 or CH-47 arrived late in the afternoon to pick up the casualties. I caught a glimpse of men carrying shapeless forms wrapped in ponchos toward the LZ but averted my eyes. I couldn’t bear to look. Captain Miller called a counsel of war with Bobby and me to give us our orders on continuing the operation. It was too late to do much that night, but the next morning we were to move out again to the north with my platoon leading. I whined and carped a little about the bad shape my platoon was in and that B Company, which had taken no casualties yet, should be taking the point. I can’t remember all the reasons Captain Miller gave me, maybe it was that B Company being newly organized was untested or maybe it was simply because my platoon was already on the north side of the perimeter, whatever it was, I had my orders so it was yes sir, yes sir, three bags full and I was back with my platoon briefing Hawkins and the squad leaders on the morrows plans. Hawkins had already redistributed our remaining ammunition and insured that our machine guns were properly placed to achieve maximum grazing fire on the ridge to our north. As we layed out our plans we all chewed on bamboo, everyone was out of water, but it didn’t help much. We were out of food too, but nobody thought too much about that at the time. God I was thirsty!

As dawn approached on the 6th we stood to, but things remained quiet and the NVA did not attack. We were to move out at about 8:00AM and quietly readied ourselves to do so. About thirty minutes prior to moving out I had the erg to relieve myself. I cannot remember having defecated once during the previous ten days, although that is something someone normally doesn’t dwell on. I would remember this time. Since we were going to move out soon, I wasn’t too concerned about relieving myself in the proximity of my position so I only moved about ten or twenty feet away and scraped out a shallow cat hole. I laid a packet of toilet paper on the ground in front of me, stripped down my ragged torn trousers and squatted over the cat hole. I wasn’t wearing undershorts, old timers had told me that wearing underwear contributed to jungle rot, but as ragged as my pants were, I wish that I had. I was constipated and it took some effort, but everything finally came out. I reached forward to retrieve my packet of toilet paper and the world exploded.

Noise! Falling forward. Face down in the earth. Noise! Trying to jerk up my pants as I slither toward my hole. Noise! Where’s my rifle? I’ve got it. I’m in my hole. Hope I don’t have shit all over my pants. Noise! It’s starting to become recognizable now. RPD’s, AK’s, B-40’s exploding in the perimeter, behind me, filling the air with invisible, deadly, tiny shards. Those menacing, evil rocket propelled grenades were seemingly busting everywhere. M-16’s, M-60’s and M-79 grenade launchers joining the maelstrom of noise. Frantically searching the slope to my front. Nothing. All the noise coming from behind me. B Company under attack. NVA firing from the ridge east of the LZ. Heavy attack from the south. Noise! Can’t do anything. Nothing to shoot at. Nothing to my front. Everything behind me. My ass cheeks clenched tight anticipating a 7.62 round or shrapnel from those godforsaken rockets to violate me. Scared beyond reason. Nothing I can do but lie there and try to make myself as small as possible. Radio crackling. Captain Miller on the horn. “Keep your heads down, artillery coming in. DANGER CLOSE!” Giant eruptions of noise on the south side of the perimeter. Danger close my ass! Danger close is supposed to be 150 meters, this stuff is right on us. The horrendous roar of exploding 155 rounds, enveloping, permeating. SILENCE!! I claw at the K-Bar knife strapped upside down on my left web gear strap and start scraping my hole deeper, which until now I had not thought possible. God I was thirsty.