By JOHN STRYKER MEYER

Few know of the secret operation conducted for eight years during the Vietnam War, hidden from the press, the public, and the politicians. This secret war was conducted under the aegis of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam—Studies and Observations Group, MACV-SOG, or simply SOG. The Green Berets, their indigenous troops, the Navy SEALS, and aviators from the Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps who died fighting in it were sworn to secrecy about SOG and its operations.

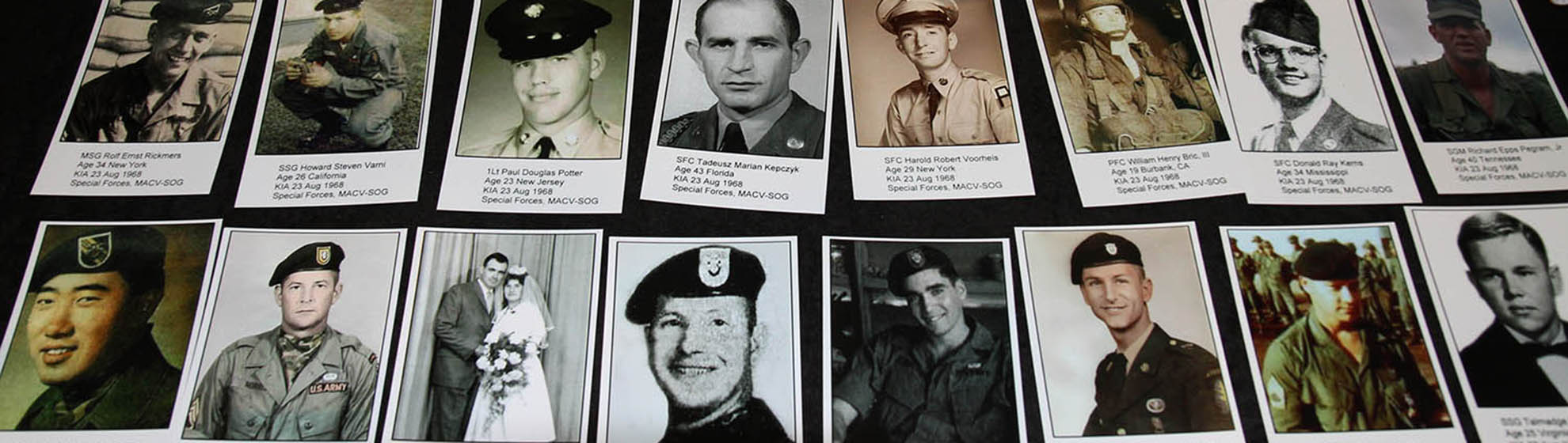

On August 23, 1968, an NVA/VC sapper attack was launched on a SOG compound in Da Nang, FOB (forward operating base) 4. Seventeen Green Berets were killed during that attack—the single largest toll of Green Berets killed in Special Forces history.

The communist forces planned the attack for more than a year. When they attacked FOB 4, they did so shortly after midnight, at a time when the compound’s base population swelled with more than 100 Green Berets appearing before a promotion board. Additionally, the monthly SOG staff meeting of all six FOB commanders and S-2/S-3 personnel was held the day before. Last, but not least, the SOG Command and Control staff stationed near the Da Nang Air Base had been moved into FOB 4, and operated out of the headquarters office.

By August 1968, SOG’s secret war had been going on for four years. Unknown to SOG brass was just how deeply the communist forces in Vietnam had infiltrated SOG and its bases, including FOB 4, which was located south of Da Nang, nestled between Highway 1 on the west, the South China Sea on the east, and Marble Mountain (which was a series of five mountains of various sizes) to the south. A POW prison, a Special Forces C-Team camp, and other military branches were located to the north.

Also unknown to SOG brass at the time, three separate ‘flash’ or ‘ZULU’ warning messages, sent by the CIA, were received by TTY (secure Teletype) at the FOB 4 communications center in the days preceding the attack. All three printed teletype messages contained only two words, according to two of the three Green Beret commo men who received and read those messages—Bill Barclay of Florida and Gene Pugh of Texas: All three messages, according to Barclay, Pugh, and other Green Beret survivors of that night in hell, were completely ignored by two key officers.

“I’ll never forget it as long as I live,” Pugh said in a recent SOFREP interview. “Monday night (Aug. 19), we received a flash message from Saigon alerting us that a ground attack on our location was imminent within the next 24 hours. I remember rushing over to (FOB 4 base commander) Colonel Jack Warren’s room and waking him with the news. A few minutes later, he arrived at the TOC (tactical operations center). For some reason or another, I couldn’t help but notice that they didn’t put any urgency to the notice, and I don’t recall the camp going on alert.”

A Second Message: “Attack imminent”

On Tuesday, August 20, 1968, “We received another Zulu or flash message from the CIA of an imminent attack on our compound,” said Pugh. “I was speaking to Master Sergeant Danny West when the message was given to me to process. Danny took the second message to Colonel Warren. Again, the time was about 2230 hours (10:30 p.m.). I don’t recall Colonel Warren coming to the TOC. West returned and went back to his desk. No words were spoken.”

Barclay added, “Colonel Warren trusted his men. In this case, he trusted that major, a major who, in my opinion, was woefully ignorant of VC/NVA capabilities and tactics. He didn’t respect them at a level that the men who ran recon did. Sadly, I was just a lowly E-3. He was a major.”

On the night of Aug. 22, because he was new to FOB 4 and still adjusting to the daily routines of camp and the comm center, Barclay arrived two hours before his midnight shift began.

“I received the third, and what would be the last, flash warning message at 22:30 hours,” said Barclay. “I’ll never forget it. Again, it was a CIA flash/Zulu message, the highest priority message there was at that time, and again it had only two words: ‘Attack imminent!’” At that moment in time, Barclay had been at the FOB 4 base and working in the comm center for only a few days, but he remembered the major’s earlier reactions to the first two flash messages.

“I had only been in camp a few days, and I was a lowly PFC (private first class), but common sense told me this warning could be serious, so I took the original copy and carried it directly to Colonel Warren. I didn’t want to take any chances.”

Barclay walked through the white sand from the comm center directly to the officers’ billets and knocked on Warren’s door. When Warren answered the door, “I apologized for disturbing him,” said Barclay, “but felt the urgency of this message wasn’t appreciated by the major.” Barclay handed the message to Warren, explaining its urgency. “Much to my utter and complete dismay, the colonel looked at me and said, ‘Not to worry, the major has this handled.’ I was stunned, and simply walked back to the comm center.”

Barclay returned to handling routine commo messages while a tired and physically drained Pugh returned to the transit barracks. There, Pugh slept in a corner room, awaiting an assignment to a recon team.

Little did Barclay and Pugh realize that, as they moved across FOB 4, NVA/VC sappers had commandeered the mess hall used for the indigenous personnel. The enemy sappers were reviewing final plans for their attack.

Why Tell This Story Now?

For more than 44 years, Barclay and Pugh kept the knowledge of those three messages to themselves, especially after no word surfaced about them in the comm center and in the months after the attack.

“Frankly, I kept the secret locked away in my mind for a long time,” Barclay told SOFREP, “because I thought I was the only one besides that major, Colonel Warren, and West who knew about them.”

“I was on the same boat as Bill,” Pugh said. “Colonel Warren and West are dead today. I don’t know if that major is alive or not. I was just happy to survive that night in hell. On the other hand, if he’s still alive, I know a few men who are still very bitter about his critically wrong assessment of our tactical situation at FOB 4.”

Barclay added, “The other reason I didn’t say anything to anyone about that message was I had lost contact with everyone I had served with in SOG. So there was nobody to collaborate with about the existence of those messages. And someone in the TOC had to have destroyed those messages after the attack. I never saw them again and no one ever mentioned them after that night.”

In 2013, long-time SOG memorabilia collector and SOG recon team historian Jason Hardy suggested to Pugh and Barclay that they talk to each other about those flash messages.

“It wasn’t until Jason linked Gene and I up at SOAR (the Special Operations Association’s annual reunion in Las Vegas) two years ago that both of us repeated what the messages said together and in unison in front of Jason.”

It was a surreal moment for the two SOG recon men, who have known each other since 1968.

When approached by SOFREP, both agreed to share their unique stories.

During SOG’s eight-year history, there were four SOG commanders based in Saigon who carried the understated title ‘chief SOG.’ At the beginning of August, 1968, Chief SOG Colonel Jack Singlaub turned over command to Colonel Stephen Cavanaugh.

Singlaub’s spec ops career was impressive: He served with the original Office of Strategic Services. He parachuted behind enemy lines during World War II, serving with the French resistance. He fought in spec ops during the Korean War and was a highly respected SOG commander during his two-year tour of duty.

Interviewed by SOFREP, Singlaub said he was heading to a new assignment on August 23, and never heard any reports about the CIA flash messages sent to FOB 4.

Cavanaugh was a highly respected officer who served with the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment that later became the 11th Airborne Division assigned to the Pacific Theatre during WWII. The 11th saw severe combat and high casualties in Leyte and in the Philippines, where Cavanaugh survived two combat jumps and received more than one Purple Heart.

When SOFREP contacted Cavanaugh, now 93 years old, about the CIA’s warning messages, he said, “I don’t recall hearing anything about three CIA flash warnings prior to the attack at FOB 4. I was new in the command and was just settling in when the attack occurred. It was one of the darkest days in SF history, that’s for sure.”

After arriving in Saigon in early August, Cavanaugh visited all of the FOBs, the supply companies, and several major helicopter support commands before going to the Philippines to help his family settle into their new home and to visit businesses that supported SOG operations.

“I was in the Philippines for two days before the attack. When I returned to Vietnam, the sergeant major was waiting for me on the tarmac. He told me that Marble Mountain had been hit. That was the first I heard of it,” Cavanaugh said.

He flew immediately to Da Nang to be briefed and to observe firsthand the carnage and damage that the NVA/VC sappers had inflicted on FOB 4.

In his recent interview, Cavanaugh said, “The thing that irritated me the most at that time was the mountain sitting behind the base, to the south. When I heard of the hit, I assumed it was launched from the mountain. Years later, we learned about the NVA/VC networks and other implements of war they stored in that mountain.”

Before the attack, Colonel Warren, who also served in WWII and the Korean War, told Cavanaugh that he had a lot of confidence in the Marines posted south of FOB 4. “That night, the sappers attacked their primary target, FOB 4,” he said. “They didn’t tangle with the Marines, to the best of my knowledge.”

Spike Team Rattler

Also unknown to Barclay and Pugh, Spike Team Rattler (SOG recon teams were code-named ‘Spike’ teams) was ordered to climb Marble Mountain and to establish an observation and listening post, said Larry “Gambler” Trimble, the assistant team leader at the time.

“There hadn’t been any team on the mountain for some time, so intel must have had some information about something about to happen,” Trimble recently told SOFREP. “We were told that snipers may be in the area, so we set up to observe for any movement by VC or NVA.”

ST Rattler had Trimble and Ed Ames, along with seven Nungs. On Wednesday, August 21, ST Rattler marched from the FOB 4 compound, through the small village to the south of Marble Mountain, then up the mountain, which had some very steep areas to climb before reaching a small ledge—so steep the team had to use ropes in two locations in order to reach the top.

From the ledge, ST Rattler men could look directly upon FOB 4, the China Sea, the Marine amphibious base, and two small Marine positions on another smaller mountain in the chain of five peaks.

he following day, Trimble took a four-man patrol around the mountainous area where the team had set up its perimeter atop the ledge. They found two different shrines, multiple caves, and trails throughout the mountain, but didn’t follow any trails inside of the mountain. After four hours, the small team returned to its perimeter.

“We observed no enemy activity, nor did we see any indications that any enemy troops had been on the mountain,” he said. “Frankly, there was much relief among us that we found no evidence of any enemy presence on the mountain.”

The team relaxed for the remainder of the day, checking its perimeter and establishing commo checks with FOB 4 and with a few Marines who were stationed on another, smaller peak on Marble Mountain. The Marines maintained a 106mm recoilless rifle at one of those slots.

Told by SOFREP about the three CIA flash messages sent to FOB 4 warning of an imminent attack, a startled Trimble said, “I’m shocked. I’m really shocked. I never heard that before. I can’t verbalize as to just how totally shocked I am. Who said that?”

When informed of Barclay and Pugh’s SOFREP interviews, Trimble added, “Over all of these years since 1968, nearly 47 years and I never heard that before. I know them and trust them and understand why they didn’t say anything about those messages, but I’m still shocked. We had daily, routine commo checks with FOB 4. Nobody said anything about an attack being imminent. Had we known that, we could have gone up to that mountain loaded for bear, with more ammo, more flares, more claymores and hand grenades. Damn, I’m shocked.”

Editor’s note: In part two, the ferocious attack is unleashed against several hundred Green Berets and indigenous troops who fought valiantly against the communists. Members of ST Rattler would fight for their lives while having a front seat to the attack that unfolded at FOB 4.

ABOUT JOHN STRYKER MEYER

Born Jan. 19, 1946, John Stryker Meyer entered the Army Dec. 1, 1966, completed basic training at Ft. Dix, N.J., advanced infantry training at Ft. Gordon, Ga., jump school at Ft. Benning, Ga., and graduated from the Special Forces Qualification Course in Dec. 1967. He arrived at FOB 1 Phu Bai in May 1968, where he joined Spike Team Idaho, which transferred to Command & Control North, CCN in Da Nang, January 1969. In October 1969 he rejoined RT Idaho at CCN. That tour of duty ended suddenly in April 1970. Today he is a program director at the Veterans Affordable Housing Program, based in Orange, CA and joined the SOFREP team of correspondents in March 2015. He has written two non-fiction books on SOG secret wars: Across The Fence: The Secret War in Vietnam – Expanded Edition, and Co-Authored On The Ground: The Secret War in Vietnam with John E. Peters, a member of RT Rhode Island. Meyer’s website is: www.sogchronicles.com.