Tony Love

This is my account of my first mission with MACVSOG, FOB II (later Command and Control Central (CCC), in Kontum, Vietnam, in spring of 1968, with SSG VanHall and SSG Davidson, and Team Iowa. Our top secret mission was to plant an anti-tank mine on the Ho Chi Minh trail in Laos. I am compelled to provide a background context. Prior to arriving at MACVSOG, I was assigned to 5th Special Forces Group Headquarters in Na Trang, Vietnam.

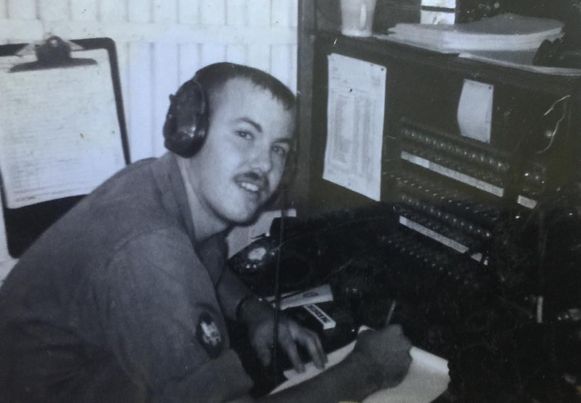

I was assigned as a radio operator in Area Defense. When the large base was under attack, the coordination of the defense happened through the radio operator. It happened twice in the four months I was there. For someone, it would have been the cushiest assignment. I , and two other radio operators, worked a twelve hour shift in the bunker, then twenty four hours off in a cosmopolitan, beach city with classic French architecture and cuisine, a restricted “American beach,” cheap “33” beer (the only brand available throughout South Vietnam), and five-dollar “short-time” whores, the two most available pleasures. I was twenty two, and I hated Na Trang. I volunteered for the war to be in the fight, not beach time, not classic French stuff, not cushey duty in a bunker. I spent my abundant off-duty time drinking “33” beer, visiting five-dollar whores, and sleeping. I noticed, except when the voice radios were on from 1800 to 0600, all I did was answer a switchboard, about seven calls per day–what a waste of a well trained asset. I went to my boss Lieutenant, and requested a transfer to this shadowy combat bunch called SOG. He didn’t dismiss it, but replied, if you find a replacement, I’ll approve your transfer; an impossible task. After a week, I went to my boss and shared my aforementioned observations about the amount of radio and switchboard traffic. I suggested, we bridge a second switchboard to his office and let the clerk work the seven calls from 0600 until the radios go on at 1800, and have a radio operator come on duty from 1800 to 0600. “You’d only need two radio operators for that, LT.” I was on my way to the fight. I was assigned to FOB II, in Kontum, in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam, and placed on Team Iowa.

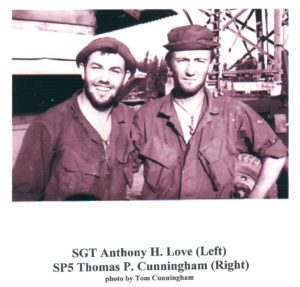

The other two Americans on Team Iowa was a seasoned recon one-zero, SSG VanHall, and SSG Davidson, who was seasoned combat vet, but like me, was new to SOG and Team Iowa. It’s an overstatement to say, I was very wet behind the ears. My combat experience was shooting pop-up targets on the range, and lots of miserable field training tests in Pineland (the name of the SF training area in North Carolina), and my cushy life in Na Trang. When VanHall and Davidson talked about the mission, they shared a lingo, a combat shorthand, only the combat experienced understand. My marching orders from them were, you’re carrying the radio, do what we tell you, and don’t be stupid. I didn’t know enough to even formulate an appropriate question. Thinking back, having me carry the PRC 25 was a mistake, but because my speciality was 05B (Morse Code radio operator), and neither VanHall nor Davidson wanted the heavy load. I was a radio operator by training, but I was unfamiliar with the interactive lingo of air support and teams. Mostly, I was the pack mule, VanHall would grab the handset and do all the talking, or tell me exactly what to say. Trusting the team lifeline, the radio to a newbie, is too risky, but not in this case. In Laos, our only limitation was we could take no more than thirteen people, and VanHall liked to go in heavy. He had about one month left on his one year tour, and this was his last mission, and he wasn’t going to take any unnecessary risks. The team loaded into two slicks. VanHall and I, the Vietnamese team leader, our interpreter, and three heavily armed troops. Iowa was a diverse team, Montagnards, Vietnamese, and one Chinese Nung.

I was too new to notice diverse teams were unusual. Davidson rode in the second slick with six more troops. The first slick flared and began to hover, we were all eager to exit. The LZ was grassy, and although the prop blast blew the grass downward, it was difficult to judge the distance to the ground. One troop left early, as soon as he jumped, we all followed. As our slick rose, the second slick with Davidson and the rest of the team took its place. As I reached the woodline, I turned to watch Davidson and five guys struggling through the grass to join us. I noticed, I couldn’t hear anything being said on the radio, so I turned up the radio as loud as I could. In the tense post-chaos, silent wait for the normal jungle sounds return, the handset blasted covey’s request for a sitrep cut loudly through the silence, followed by me answering in a loud, above normal speaking voice. VanHall grabbed me, eyes wide, and yell-whispered, turn that fucking radio down, and be fucking quiet! We had never talked or trained about noise security. I was fucking clueless. The hot and humid, thick, triple canopy jungle was dark, damp, viney, buggy and smelly-rotten, and stifled our movement. It was difficult to maintain noise discipline with thirteen people. A six man team is more controllable and silent. In the afternoon we discovered two abandoned bunkers on the edge of large open area. VanHall said they were used to observe or attack a team using the open area as a LZ. VanHall pulled two “toe poppers” from his rucksack and planted them in the floor of each bunker. Seeing those bunkers, was my rude message, “this shit is for real.” It wasn’t my Special Forces training that kicked in. It was my childhood years of stalking rabbits and quail, BB gun battles, hide-and-seek, Boy Scouts, and running from the police after pulling some prank that kicked in. In that moment, I became a recon guy.

On our second day, we neared our objective, the Ho Chi Minh trail. It wasn’t easy. Our early morning involved moving down a steep hill, through the narrow valley, and by noon arrived at the hill top. We planned to find a thick hiding spot, remain there until night. While the rest of the team would secure the rally point, VanHall, our Vietnamese team leader, the interpreter, and another troop would, leave their gear and S trip down to weapons and ammo. Two men would secure the far side of the road, one on our side, VanHall would plant the anti-tank mine, and they would withdraw back to the rally point, where we would remain until daylight and withdraw. Suddenly we heard voices, speaking Vietnamese, coming directly from the area VanHall planned to breach the road. It surprised us, because it was loud enough for us to hear. VanHall asked the interpreter to translate. “What are they saying?” “They say, they come kill us,” was his reply. Immediately we began to hustle down the hill back into the valley and as we were nearing the top of the where we started, we began to receive fire from the top of the hill across the valley. We weren’t trying to be quiet, we were moving as fast as we could. I’d heard a lot of gunfire, but I had never heard a bullet whizzing past. It’s a sound I’ll never forget. VanHall yelled for me to contact, the relay site, Leghorn. VanHall wisely told us not to return fire. We were getting fire in our general direction, but no one had gotten hit. If we had returned fire, we would have given away our position. “Leghorn, this is lockjaw. Over. Leghorn, Leghorn, this is lockjaw. Over.” I got nothing but silence. I tried again and again. We were running, bullets were whizzing by. We ran toward some rocks we could use for cover. Running towards the rocks and calling for Leghorn as I ran. About five feet from the rocks where VanHall and Davidson had taken cover, Leghorn responded, lockjaw this is Leghorn. Over. I noticed, it was that spot, and only that spot, five feet from the safety of the rocks.

If I moved one foot in any direction, I lost contact. From the safety of the rocks, VanHall told me our location and requested air support and extraction. Until I was assured Leghorn had support on the way, I stood in the open, a sitting duck. After telling Leghorn we were going to lose contact when I moved, I made it to the relative safety of the rocks. The NVA was hesitant to leave the top of their hill into, what would have been ‘death valley.’ The incoming fire rose and fell in volume and came close, we never returned fire, and remained safely behind our rock cover, until air support arrived about 1600. VanHall grabbed the handset and directed the air support. We had A1-E, fighter bombers on station. VanHall worked them. He mainly had them drop their ordinance from where we received fire and worked it down to the road. The pilots were getting secondary explosions from the roadway. Evidently, we had stumbled upon a daylight truck park, a place where supply trucks were hidden from sight during daylight hours. VanHall kept working the A1-E’s, but covey was worried it wasn’t safe to attempt a withdrawal, and wanted us to remain overnight (RON). As a safety measure, they dropped cluster bombs a safe distance and clearing any enemy soldiers trying to flank us or approach from the rear. VanHall wasn’t happy about staying the night without support. I don’t think any of us slept. I lay awake all night and counting the secondary explosions from the direction of the truck park. Each one would sounded like a rumble, like the earth was growling, and the sky would brighten and diminish into darkness, followed by another, then another. By the end of the night, I counted fifty two. Shortly after daybreak, covey arrived to take us home. Covey gave us directions to a small LZ, where we were to be extracted on strings. The A1-E’s prepped the LZ and widened it with the bombs he had on board. He spent extra time doing a lot of prep because he saw a secondary explosion on the LZ. We arrived to find a small hole in the triple canopy, and the floor of the jungle peppered with bomb craters, still warm and smoking. We came out in two slicks. The rest of the team on the first chopper, and VanHall, Davidson, the Vietnamese team leader, interpreter, another troop, and me on the second.

After SSG Don Davidson, my one-zero of Team Iowa, started flying covey, I was made one-zero of Team Iowa, but I had no one-one. Two came and went; SP4 Angster had a box of blasting caps blow up in his face, and the other guy decided he didn’t want to do recon and got assigned to the commo bunker. SFC Barnes was running the mess hall/club, and was itching to do some missions. So, they gave him Team California, and made me his one-one. We were given some time to bond with the team, and each other. We did training at the range; immediate action drills, claymore training, and planting toe poppers (antipersonnel mines). It was mainly live-fire team building.

Barnes was literally a larger than life guy. He had long red hair, and a giant red handlebar mustache, a ginger Goliath. It was rumored that he had played Center for the Boston Patriots. He had a respectful disrespect for officers, and was smart as a whip. His close-to-the line, wise-cracks to officers’ timid requests to cut his hair or mustache, left the poor officer confused and flabbergasted. He was crossing the compound hatless, and a Major commented, “Sergeant Barnes, aren’t you afraid your head will get sunburned?” Barnes replied, “No way, Major. My hair is too fucking long.” He mostly out-thought them. He took me under his wing, and I was happy for the freedom to smuggle whores into camp, steal jeeps, impersonate myself as a very young E7 in Pleiku with Barnes to pick up supplies for camp, and do all sorts of mischief while protected by Barnes. Barnes knew an alcoholic cook in the 4th Infantry Division. He traded cases of vodka for cases of steaks. The 4th ID legs ate hot dogs cooked by a drunk, we ate steak. I never felt so comfortable on-base, off-base, or in the field.

We were assigned a mission in northern Cambodia, near the border of Laos. Our primary mission was an area recon, our secondary mission was a prisoner snatch. We geared up, and prepped for the mission. I joked with Barnes that, if he got hit and couldn’t move, I’d cut him up in man-portable loads, or leave him and take his Rolex. He had two, a Submariner and a gold Rolex–he wore the Submariner to the field. Anyway, I digress.

I remember our mission was in Cambodia, and not Laos. The rules of engagement in Cambodia said, we could only take six guys, and fast movers (jets) or A1E’s (WWII fighter bombers) for support were not allowed. We could take up to 13 guys into Laos, and get fast movers and A1E’s with all their ordinance (High Explosive) HE bombs, cluster bombs, napalm, a 20mm cannon), and a long station time. The pilot could drop napalm in your pocket, if that’s where you needed it. In Cambodia, we were limited to gunship mini-guns and rockets. The foliage was like the targets I ran in Laos; thick, triple canopy jungle, dark, damp, and buggy. Barnes wanted to go in at last light. Frankly, that scared the shit out of me, and I argued against it. If you go in at last light, and get in trouble, there’s not much time to get air support, and exfilled. Barnes insisted, I saluted.

About 3 PM, we loaded on the slick, and left for our target. I was still scared shitless about the last light insert. I remember these three green hills on the left on your way to the mission. They looked like three perfect, green breasts; beautiful, peaceful, maternally comforting. When I saw them, my head would click into hyper-vigilant, mission mode. Coming back, with the hills on my right, they whispered, you’re safe now – steaks, whisky, and whores to follow. After a long ride, the slick flared into the LZ. Once he got to a hover about 6 feet from the ground, I jumped, and everybody went with me. I remember thinking it was too high for Barnes’ weight, but not so. He hit and rolled, PLFey (parachute landing fall). We hit the ground hard and ran (3 o’clock from line of flight), and hit the wood line. With the chopper gone, we set up the defensive perimeter. In silence, we had a long, tense wait for the normal jungle sounds to resume.

We circled the LZ looking for man-sign. There was some grass broken, and we decided it was an animal bed. We kept alert for a possible tracker, and released the air support. We started to look for a RON (remain overnight) site. I remember covey sarcastically joking about missing supper. It was dusk, and Barnes told me to release the covey. I didn’t agree because we hadn’t found a RON site, and we were still moving. We finally found a site, settled in, and tried to sleep through our adrenaline high.

In RON, we slept in a circle holding hands. We could pull an hour of guard duty, then squeeze the hand of the guy to your right, and pass guard duty to him. If something happened, squeezing both hands waved around the team and silently awoken everyone. Finally, Barnes, who arranged himself to be the pre-dawn guard, squeezed us awake. We geared up and started toward the valley from the small knoll where we RON’d. We moved quiet and slow.

The bottom of the valley stank of the stagnant water which lay in small pools on the jungle floor. One of the Yards found a fresh NVA boot print. We looked, but couldn’t find another. We took pictures, then started up the steep hill. It was difficult, slow moving. We didn’t get good footing until we neared the hilltop. It was especially tough for Barnes, but I was amazed by his agility and silent movement.

On top of the hill, the wood line broke to reveal an abandoned fighting complex. It featured a zigzag, six-man fighting trench, two, two man bunkers, and a two-man, sniper/lookout platform about 15-20 feet off the ground, constructed of bamboo and accessed by a bamboo ladder. The foliage was completely dead from a long, well-used occupation. Ironically, except for the sniper platform, we used those fighting positions to defend the hilltop for about an hour of intense combat before air support arrived. Barnes and I fought from the zigzag trench, and our Yards from the bunkers.

The Yards secured the perimeter, we surveyed the site, Barnes mapped it, and I took pictures. We spent a long time there, maybe an hour. It was getting to be about 10 AM when Barnes signaled for us to go, and we began to move down the hillside. Compared to the climb up, it was a gentler slope into a flat valley.

We were about forty meters into the wood line when coming from our right, we heard someone speaking Vietnamese. We set up security. Barnes, the interpreter, and I crawled to about ten meters away from two NVA. One cranked a generator, and the other was speaking a number coded message into a radio. The NVA radio operator had on a headset, and as he and his “juicer” were intent on their activity, we got close. Barnes signaled to withdraw, and we moved back to the hilltop complex. Barnes started planning for a prisoner snatch. I called covey for air support. Covey said, another team was in trouble and was being exfilled. We’d have to wait.

Barnes planned for a six-man defense of the hilltop. He had us set up claymores aimed at likely avenues of approach. In retrospect, that saved our lives. During the fight, there were lulls, probing, then, hard assaults. Each assault came from the locations Barnes had anticipated. It was like they were running straight into the claymores. Everyone, except me, dropped their packs in their fighting position. I kept the radio, and waited on the OK from covey. Finally, we finished our set-up. All in, we waited about an hour for the signal to go.

Our plan for the snatch was to leave one man on the hilltop. The rest of us would move as close as we could to the radio operator and his juicer, get on line and as close as we could, overwhelm them, kill the juicer, but not harm the radio operator. We planned to physically overpower and subdue him, and move him to the hilltop. The plan from there was iffy. We believed we had air on station, and we might be able to make it back to our original LZ. We knew a radio of that size and a generator meant there were lots of folks nearby. I remember Barnes saying, “We gotta get that guy. The radio operator knows everything! S1 (admin) will shovel medals at us, and we’ll get a week R&R in Taipei.” By this time, whatever Barnes said, I believed. Before he mentioned medals and R&R, I had not had a ‘meta-thought,’ since I saw the three green hills just after lift-off – thoughts about anything outside the box of what was happening in the moment, or might happen in the immediate future, had no place in my brain.

The covey came up, “OK, Razor, go grab that ‘dime.’ The air (support) is leaving Pleiku.” “Razor” was my code name, and “dime” was the code word for prisoner snatch. What covey didn’t know was that the choppers were refueling, NOT on their way. Actual ETA was about an hour away.

Noonish, we moved into position, and found absolutely nothing. The radio operator and his juicer were gone. We withdrew, to figure out where they went. We found a position where we could look down into the valley. About fifteen to twenty meters away, I saw a ‘poncho hooch’ with a small smoking fire, and a man swatting mosquitos, his AK 47 leaning against a tree. I alerted the team. Just then, I noticed another hooch, and another, and another. I did a quick count of about forty hooches, and alerted the team again, pointing to one after another. Assuming we had air on the way, Barnes thought “let’s fuck these guys up.” He shifted us on-line, fight ready. We were visible, one giant standing in the middle of five little guys, guns at the ready. The NVA swatting mosquitos spotted us and made a move for his AK. I opened up, and as he fell, everyone opened up, spraying full auto into the valley. Barnes started throwing grenades. I threw one, but the targets were out of my range. Barnes could chunk them a long fucking way. I went back to shooting bursts in the general direction of anything that moved. We started taking return fire, increasing in volume. Barnes called retreat, and we ran the forty meters back to our fighting positions.

Barnes took my radio, and that was new to me. The best part of lugging a PRC 25, was calling in the air strikes. It’s a godlike feeling — you speaks to the angels, and suddenly explosions and death land wherever you direct it. Barnes talked to covey and shoved the radio back to me, stating, “The air won’t be here for an hour. We are so fucked.” It took about five minutes before we were probed the first time. A few pot shots at first, we held fire. Then came the first assault with heavy fire. We let about five guys get close before we opened fire and blew a claymore. With lots of screaming and yelling, they withdrew. A few minutes later, we got the same thing from a different direction. Barnes was cranking off the claymores, the rest of us engaged targets as they revealed themselves. We could also hear a lot of activity in the valley and suspected they were going to attempt something from the unprotected steep side of the hill. I told the covey that I wasn’t sure how much longer we could hold out. Covey said he could give us four of his six willie peter, marker rockets. I called for them in the valley. I watched him roll and start his approach. He passed directly over our heads, nose into the valley. He pulled out of his dive, and his rockets fired off into the distance–a hang fire. He said he’d try again, but he could only give us two rockets, and had to save his last two for when the air assets arrived. He made another run, and this time he was on target. Lots of screaming and activity in the valley – the white phosphorus was fucking them up. From then on, all we got was probing fire. With no more claymores, Barnes and I ran back and forth in the zigzag trench as targets showed themselves. The Yards were kicking ass from their bunkers.

Finally air assets came on station. I was almost out of ammo. I carried 22 magazines. I tossed about five or six mags to the Yards fighting from the bunkers, and only had a couple left. Barnes took the radio and worked the gunships. The rest of us continued to clear close targets that popped up. I left the trench and dropped some grenades down the steep slope, and sprayed downhill in case they were trying to come at us from the steep side. Barnes had the gunships spray completely around us.

Finally, things quieted down enough to attempt an exfill on strings. Barnes gave me the radio and began to rig the rucks for exfill. Barnes and I snap-linked them together to ride under my seat. The slick came in and dropped six strings with rigs. The rigs had two leg strap loops and an adjustable loop belt that fit around the waist. The Yards and I were small, so we dropped the waist loop over our heads and web gear, and pulled the leg loops over our boots. (You’re actually supposed to put it on like a pair of pants, stepping through waist loop into the leg loops.) I don’t think Barnes trained on strings, and it was new to him. Barnes followed our lead, waist loop over his head and web gear, but because of his size, he struggled to pull the leg loop over his boot, but got it. A different story for the second leg loop. It got stuck on his heal, and would not budge. I had to help, and it was a hell of a struggle. The chopper continued to hover, while the pilot screamed over and over, “Let’s get outta here!” Finally, I gave the OK for lift out. We got a little beating from the trees. It was about 5 PM.

I can’t remember the A Camp we landed in, but it was probably Ben Het. They had their Yards in a ‘catch circle’ to keep us from smashing into the ground. It was a lot like that kid’s toy with small bowling pins in a circle and a ball on a string attached to a stick in the center. The ball is tossed and swings around knocking over the pins. That’s what it was like with Barnes on the string. He was bowling over any Yard who tried to catch him or us.

On the ground, off the strings, and into the chopper. Barnes looked at me and I looked at him, nothing was said. We knew we got away with a big one. I spotted the green hills on the right a little over twenty-four hours after I first saw them after liftoff. I dropped my gear, showered, went to the club, and got drunk.

I often wonder what the guy swatting mosquitos thought when he saw us. Barnes, with his OD bandana around his big fucking red head, long hair, and his giant red Fu Manchu mustache. The swatter had remained cool, slowly stopped swatting, and inched toward his AK. No matter what he thought, he died with that.