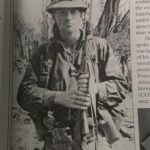

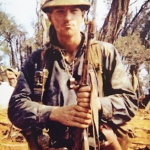

Sergeant First Class Jerry M. Shriver

If you ask any man who served with MSG Jerry “Mad Dog” Shriver, they’ll tell you he was more of a warrior than a Soldier: a man wholly dedicated to warfare and violence. He was the distilled essence of war in its most primal, basic nature. He was the best ally to have, and the most dangerous enemy to face. The men who fought and served alongside Shriver could describe him best. Medal of Honor recipient Jim Fleming, described Shriver as, “the quintessential warrior-loner, anti-social, possessed by what he was doing, the best teammate, always training, constantly training.” On another occasion Fleming stated “Shriver convinced me that for the rest of my life I would not go into a bar and cross someone I didn’t know.”

Like many legendary figures of history, Shriver’s backstory is confusing as he just seemed to just appear one day. He was born on September 24, 1941, in De Funiak Springs, in Florida. Little is known about Shriver’s life, but what we do know is that he attended Airborne school, spent a short stint in the 101st and also attained his Green Beret at a very young age but then he disappeared from history again.

In 1966 he appeared in Military history again as a Staff Sergeant in the legendary MACV-SOG. MACV-SOG was an asymmetrical warfare task force assigned to carry out top-secret missions throughout the South-East Asian theater during the Vietnam war. During his time in Vietnam he earned his Nickname “Mad Dog” from his enemies. Radio Hanoi, a NVA propaganda radio station, announced a $10,000 bounty for his head. That’s approximately $70,000 nowadays adjusted for inflation.

He was a platoon sergeant of one of the secretive “Hatchet Force” units. The units usually consisted of three American MACV-SOG members and twenty to thirty handpicked locals who were trained in the science of unconventional warfare. Every man in that unit was a dedicated, battle hardened warrior and could only be led by the best. The Hatchet Force’s mission statement is as follows: “probe the border areas and look for a fight”. In other words Shriver would lead his men behind enemy lines and kill or capture all that they could find. In one engagement where his small team was encircled by waves of NVA soldiers Shriver contacted his leadership with what would become one of the most famous radio transmissions of the war: “No, no…I’ve got ’em right where I want ’em – surrounded from the inside.”

Shriver, the definition of a warrior, cared little for pomp and circumstance. He’d been awarded a Silver Star for an engagement where he volunteered to hold off waves of enemy soldiers with disciplined small arms fire and accurate calls for Close Air Support while his team was hoisted up through the jungle canopy one by one. He only evacuated once every single man was rescued. He was also awarded the Soldier’s medal for Heroism, Bronze Star with two oak leaf clusters, Bronze star with 4 Valor devices, Air Medal, Army commendation medal with OLC, Army Commendation Medal with Valor device and Purple Heart with two OLC. MSG Shriver also earned the Combat Infantryman’s Badge among many others. However, he didn’t care about medals or awards as colored bits of fabric any shiny metal meant nothing to him.

What he did care about were his men: he Montagnards. His Montagnards. The Montagnards were a group of fiercely independent tribes of people who lived in the Vietnamese highlands. They were known for their dogged tenacity, bravery in battle and almost supernatural tracking abilities. They were an ethnic group of some of the best jungle scouts and reconnaissance soldiers to ever exist. Shriver respected and cared deeply about his Montagnards, and they in turn came to revere him. Shriver didn’t care about money. Except for what he spent on essentials and food, nearly all his money he earned during his deployments were spent on his men and their families. He’d collect food, clothes, and other donations from soldiers to give to the Montagnards’ villages who so bravely supported him. While he had some American friends, he spent most of his time with his Montagnards. He was the only American at CCS (Command and Control, South) who lived in the Montagnard barracks. He’d routinely eat with them and drink from the communal pot of Rượu cần, a type of alcoholic fermented wine.

Shriver was eccentric. When he wasn’t training or fighting he would often be seen walking around CCS in a blue velvet smoking jacket and derby hat. Not surprisingly, he was also always armed. It wasn’t unusual to see him with four to six pistols or revolvers on his person. Shriver was also often seen with his dog, a large German shepherd named Klaus, who he adopted at some point during an adventure in Taiwan. When he wasn’t on mission, he was seen walking about the base with Klaus at his side.

One night, while Shriver was away on yet another killing excursion, some recon men, in a mood for a cruel prank, force-fed his dog a bunch of beer in the NCO club. Klaus unfortunately became sick and defecated on the floor. The Recon men then rubbed poor Klaus’s nose in his excrement before kicking him out of the club. When Shriver heard how these men abused his companion, He walked into the NCO club. He grabbed a beer, chugged it, removed his smoking jacket, pulled out one of his .38 special revolvers and placed it on a table. He then dropped his pants and took a shit on the floor of the NCO club. He then faced the crowd of Recon soldiers and said “If you want to rub my nose in this, come on over.”

Not a single man came forward.

Shriver was a walking arsenal. On top of the multiple pistols he carried on his person, during missions he was rarely seen without his sawed off shotgun, suppressed M3 grease gun or a Thompson, and satchels of hand grenades or other explosives. Once he was asked If he’d rather have a CAR-15 or M16 instead and he responded “No sir, them long guns will get you in trouble and besides, if I need more than these, I got troubles anyhow.”

He started his deployment in 1966, and for almost 3 and a half years he kept extending his deployment. He spent over 1,000 days in country. In some sense, I don’t think he knew how to shut it off. He became War Eternal. Instead of debriefing and relaxing after a mission, Shriver would sneak out and tag along with another team for another patrol. Shriver once took leave to get some R&R… that’s what he told his superiors anyway. Instead he quietly traveled to Plei Djerang Special Forces camp to hook up with another Special Forces team to fight with them for a couple weeks.

In 1968 he was forced back state-side for a mandatory R&R period. His comrade, Green Beret Larry White hung out with Shriver. White stated that Shriver shopped around to find a Marlin Lever action rifle chambered in the powerful .444 Marlin Cartridge. Just so you guys understand, a .444 Marlin throws a 240 gr .44 projectile downrange at around 2,400 FPS. For reference, a .44 Magnum revolver usually pushes a 240 gr pill at around 1,200 FPS. At 200 yards away a .444 Marlin hits harder than a 4 inch .44 magnum at point blank range. People fucking hunt Grizzly and Polar Bears with .444 Marlin. Shriver had his .444 Marlin shipped back to MACV-SOG headquarters at CCS. He jokingly said he used it to “bust bunkers” but he liked how the massive exit wounds would strike fear in his enemies.

Though he kept up a tough exterior, Shriver was still human, and three years of non-stop war was getting to him. He had too many brushes with death. Every day he went out was another flirtation with the Grim Reaper. But he also felt a responsibility to his men, he couldn’t just quit on them. He confided to his close friends that he did fear death and he felt that his luck had run out. He wanted to quit but didn’t know how. He wasn’t wired that way. It made him what he was, the relentless warrior, the legendary soldier, the revered leader. He was a warrior to the bone and it was his fundamental philosophy to fight. It had brought him to this jungle and would take him to whatever death, kind or cruel, that the fates had in store for him. It’s heartbreakingly sad in its own way. Shriver would remain true to himself until death claimed him.

On the morning of 24 April 1969,the SOG raider company lined up beside the airfield at Quan Loi, South Vietnam, 20 miles from the secret lair of the Central Office of South Vietnam. The COSVN was the North Vietnamese political and military headquarters inside South Vietnam. But it wasn’t a hard structure like the US pentagon. The COSVN constantly took form in villages all across south Vietnam. It was an ephemeral target. Because of the secretive nature of their mission, Shriver’s unit was denied most of their Aerial assets by the US State Department. Right before he got into his chopper Shriver turned to his friend who was seeing him off and said “Take care of my boy” referring to Klaus. As the SOG raider unit took off, the first helicopter was turned around because of mechanical problems, so Shriver’s 1st platoon and 2nd platoon continued on alone.

As soon as they landed, they were subjected to vicious arcs of emplaced machine gun fire. Overlapping fields of fire from heavily reinforced concrete bunkers stitched across the LZ. From the back of the LZ, Mad Dog Shriver radioed that a machine gun bunker to his left-front had his men pinned and asked if anyone could suppress it to relieve the pressure. Taking shelter in a crater, Capt. Cahill, 1st Lt. Marcantel and a medic, Sergeant Ernest Jamison, radioed that they were pinned, too. Then Jamison dashed out to retrieve a wounded man. Tragically, he was targeted by machine gun fire and killed.

No one else could engage the machine gun that trapped COSVN Raiders. It was up to Mad Dog and his Montagnards. Shriver radioed that he was going to try and flank the MG positions. His half-smirk steeled the resolve of his fighting Montagnards. Then they were on their feet charging. Shriver was his old self again, fear replaced by confidence. He aggressively moved to enemy gunfire, 5 of his handpicked mountain men running with him as they dashed through the flying bullets, into the treeline, into the very mouth of the COSVN.

Mad Dog Shriver was never seen again.

At the other end of the LZ, the battle raged on. Sergeant Jamison’s body lay just past where Capt. Cahill and 1LT Marcantel took shelter from a torrent of MG fire. When Cahill lifted his head, a round hit him in the mouth, deflected up and blinded him in his right eye and left him unconscious and bleeding from his wounds. In a nearby crater, 2nd Platoon’s Lt. Greg Harrigan directed helicopter gunships who’s rockets and mini-guns were trying to suppress the aggressive NVA. Harrigan reported, more than half his platoon were killed or wounded. For 45 minutes the Green Beret lieutenant kept the enemy at bay with accurate gun run requests before he too was hit and killed.

Hours dragged by. Wounded men laid untreated, bleeding out in the sun. Several times, the Hueys tried to MEDEVAC their wounded but each time heavy fire drove them off. Finally a passing Australian twin-jet bomber from No. 2 Squadron at Phan Rang heard the SOG Raider Company’s desperate calls for help on the emergency radio frequency, and broke off from it’s flight plan. Ignoring the fact that the request came from within the supposedly “neutral” Cambodian border, the Australian crew dropped a payload on the enemy positions. By that point, only 1LT Marcantel was still directing calls for CAS, eventually calling in danger close missions so close that they wounded himself and his surviving nine Montagnards. After 8 hours of intense battle, three Hueys raced in. Of the 18 members of the Hatchet platoon, two were confirmed dead, ten were wounded and six, including Shriver, were listed as MIA.

The US Army and ARVN forces hit the COSVN location hard and in force a week later. While they found and neutralized a large logistics base with nearly 200 storage bunkers containing over 1,200 individual weapons, around 200 crew-served weapons, 30 tons of food,and vast amounts of ammunition and explosives, the ever elusive C2 node of the COSVN disappeared again.

In the weeks that followed, Radio Hanoi repeated propaganda pieces of how they captured and Killed Shriver, but they never showed any proof. One year after the COSVN raid, the NSA intercepted enemy messages warning of impending SOG operations which could only have come from a mole within the SOG headquarters. It was long after the war ended that it became known that the North Vietnamese had penetrated SOG, inserting at least one spy in SOG whose treachery killed many Americans, including the COSVN raiders.

Shriver was less than three weeks away from finishing his third tour of duty. He was just 27 years old when he was officially listed as MIA (Missing In Action). He left behind Klaus, a little over a dollar in his account, and his prized smoking jacket which would hold a prominent place of honor in the camp’s club. The following inscription was displayed underneath the silk smoking jacket:

“In Memory of Sergeant First Class Jerry M. Shriver

Missing in Action 24 April 1969.”

In 1974, the then Secretary of the Army gave Shriver a ‘Presumptive Finding of Death,’ and his file was permanently closed even though his body was never found. He was posthumously awarded a second Silver Star and promoted to Master Sergeant.

However there remains a myth among SOG veterans and Shriver’s brave Montagnards that any day now, “Mad Dog” Shriver will walk out of the Jungle as he has hundreds of times before and bellow out “Hey, Where’d everybody go?”

Because as we all know, Legends never die.

Andy‘s NSFW content at @call_me_ak on Instagram.

Jerry Shriver’s Recon Missions with Valor Awards

On October 8, 1966, Sergeant First Class (SFC) Jerry Shriver was moving his team through the jungle when he heard two rifle shorts nearby.”…He quickly called the supporting aircraft (155th AHC) and notified his base that his mission had probably been compromised. He discovered a rail junction and deployed two men for security while he moved down one of the trails with the rest of his team. A short time later, the security elements detected a Viet Cong force following the trail and opened fire, wounding one insurgent and forcing the rest to flee. SGT Shriver quickly led his men back to the jungle and moved along to pursue the wounded man. He spotted the soldier moving away from him and circled in front of him, capturing him without firing a shot. He quickly led his team toward an Landing Zone (LZ) but two large enemy forces moved in from opposite sides. Hearing his comrades closing in, the prisoner dashed into the jungle to warn his forces. Once again SGT Shriver ran after the prisoner in an attempt to capture him before he pointed out the team’s positions. The VC out-distanced him but Shriver stopped him with accurate fire. He then returned and deployed his men into defensive positions when the hostile soldiers surrounded the team. The helicopters quickly arrived and drove off the insurgents, enabling a safe extraction….” (Per USARV GO#5801, dated 11/10/67.)

Jerry Shriver’s Recon Missions with Valor Awards

The Silver Star citation of Shriver describes part of the actions of the October 26-27, 1966 mission: “…. Staff Sergeant Shriver distinguished himself by exceptionally valorous actions on 27 October 1966 while serving as assistant team leader of a four-man Special Forces reconnaissance team on a combat mission deep in hostile territory. While moving through thick jungle terrain, his team was attacked by a numerically superior Viet Cong force. SGT Shriver and his men succeeded in repulsing the first attack and immediately pulled back into a defensive perimeter. He then moved out of the perimeter to reach the body of a dead insurgent in an attempt to gain intelligence material. The Viet Cong had removed all equipment from the body so he moved back passing within ten meters of two insurgents. He attempted to make radio contact with friendly forces but was unable to in the thick terrain. The enemy forces soon surrounded his team but he directed heavy fire on them and repulsed their numerous probes. Finally making contact, he called in air strikes on the Viet Cong positions to cover evacuation operations. Because of the terrain and heavy firing, the helicopters were only able to hoist one man at a time. SGT Shriver volunteered to remain on the ground to cover the operations and directed deadly fire on the concentrated attacks by the hostile soldiers. Ignoring the hail of bullets striking around him, he fought furiously until all his men were aboard….” (Per RV GO #4999, dated 10/01/67.)

Jerry Shriver’s Recon Missions with Valor Awards

On 10 August 1967, Staff Sergeant (SSG) Shriver’s “…team was surrounded by a large VC force while moving through dense jungle [near Plei Djereng] in search of suspected enemy bases and infiltration routes. The insurgents were unsure of his exact position and fired as they advanced in an attempt to force the team into the open. SSG Shriver calmed his men and immediately called for heavy air strikes on the enemy ranks. As the ordnance pounded the jungle around him, he completely ignored his own safety and led a breakthrough under a hail of bullets and shrapnel to a nearby Landing Zone. Braving withering fire, he deployed his men in a defensive perimeter and fought furiously to reply the repeated assaults by the VC until rescue helicopters arrive…” (SSG Shriver was awarded the Army Commendation Medal for Valor on 10/21/67.)

Jerry Shriver’s Recon Missions with Valor Awards

On 10/23/67 Recon Team Brace led by SFC Jerry Shriver crossed into Cambodia then moved to YB634485 where an abandoned company-size bivouac site was found. The team was forced to move deeper into Cambodia to YB633462 where it was extracted from Cambodia under emergency conditions. Four armed helicopter sorties flew in support of the ex-filtration with unknown results.

“…SFC Shriver distinguished himself by exceptionally valorous actions on the afternoon of 10/23/67 while leading a reconnaissance patrol deep within enemy controlled territory. Shortly after receiving a resupply, SFC Shriver was spotted by a small enemy element. He attempted to trick them into approaching, trying to capture a prisoner. Unfortunately another enemy soldier came from another direction and recognized the reconnaissance team for what it was, and not friendly guerrillas, Sounding the alarm, he opened fire and the others followed suit. Ordering his team members to throw hand grenades so as not to completely disclose their position, SFC Shriver and his team attempted to break contact with the now platoon size enemy element. Boxed in on three sides, the team suddenly found itself backed up against a large lake, making further movement impossible. At that moment SFC Shriver contacted the Forward Air Controllers (FAC) and told him of their now desperate situation informing him that he was in contact with an estimated enemy platoon, with the enemy yelling that the rest of the company would join them soon. The FAC committed two USAF gunships for support, and SFC Shriver coolly directed their rocket and mini-gun fire into the enemy ranks, now only thirty meters away and forming for an on-line assault. In the midst of the furious engagement SFC Shriver calmly adjusted the supporting fire to within twenty meters of his position until the enemy began falling back…” (Per 5SF GO 68/0011 – dtd 02/12/68.)

Jerry Shriver’s Recon Missions with Valor Awards

On 05/13/68 Platoon Leader CPT Walter A. Hess and SFC Jerry M. Shriver took part of reaction platoon on a reconnaissance and ambush patrol as a part of Omega Recon and Reaction Patrol Team “Stud”. During the mission, “…Sergeant Shriver distinguished himself on 13 May 1968, while his patrol was surrounded and pinned down by a large enemy force. The patrol leader was wounded in this action, and SGT Shriver quickly took command of the patrol. He gallantly exposed himself repeatedly to the withering hostile fire of the enemy in order to organize a defensive perimeter and encourage his troops. He then began directing helicopter gunship attacks against the enemy and again completely disregarded his personal safety as he advanced to an extremely dangerous exposed position in order to accurately observe the air strikes. He then led his troops in a skillful withdrawal to an extraction-landing zone. Upon arriving at this point, he again fearlessly exposed himself to the fire of the pursuing enemy in order to clear the area of high brush and other obstacles. His courageous actions during this battle resulted in 12 enemy KIA and an unknown number KBA.” (Per 5th SFGA GO #2067, dtd 11/28/68.)

Jerry Shriver’s Recon Missions with Valor Awards

The only written records we have of this B-50 Omega recon team mission on 11/04/1968 is the BSV citation of SFC Shriver whose excerpt shows, “…SFC Shriver was commander of a recon team inserted on an LZ when they came in contact with an estimated battalion-size enemy force. SFC Shriver took three men of his team and went on line delivering a volume of fire on the enemy killing four and wounding 26. Shriver gave cover to his radio operator as he contacted gunships while at the same time he was directing the fire of the gunships. At this time a helicopter landed to pick up the team and encountered machine gun fire. SFC Shriver led his men to another landing zone. Still under fire he was placing gunship fire on the enemy while enroute to the landing zone. When the team reached the new LZ rope ladders were drop from the helicopter for extraction. Shriver personally covered his team from enemy fire while they entered the helicopter. Once all the team members were aboard, he hooked himself to the ladder by use of a snap link in order to expedite the extraction. Clearly exposed to enemy fire, SFC Shriver continued to fire on the enemy from his dangling position until the helicopter was away from the enemy fire…” (Per 5th SFG(A) GO#0239, dtd 02/25/69.)

Another member of the Air Support by the 20th SOS in this mission is from SGT Ron Winkles from his memory and from articles he wrote some time after the mission. “On November 4, 1968, I was flying as left door gunner on an insertion mission for a six-man recon team out of Duc Co. The team leader was SFC Jerry M. Shriver. This particular insertion occurred about 50 km southwest of Duc Co along the Ho Chi Min trail. Our slick was flying lead with the team. Everything went well, and it was a beautiful, clear, sunny day. I can remember thinking when we pick these guys up in a couple days, the election will be over back in the states and maybe Nixon will be elected and start getting us out of this mess. To the contrary, we hadn’t no more than cleared the tall trees of the LZ when we heard the call for an extraction. Then, our radio went dead. The radio stayed dead until we returned to Duc Co later that day, but in the meantime, we had to do the extraction. We put them in, so we got them out. This was the policy of the 20th Special Operations Squadron. A little thing like a non-working radio was a piss poor excuse for not getting your team out, and we didn’t have any excuse makers in our crew. You would have been laughed out of the unit if you even suggested such a thing. We did have a working intercom, and that was all we needed.”

“The pilot caught a bunch of air about 6,000 feet, and he told me and SSG Jim O’Goreman, the right door gunner, to look for smoke or a flasher panel. In just a minute or two, I saw the bright international orange flasher panel open and close. SSG O’Goreman and I were out of the skids, and we directed the pilot down into the LZ. I noticed the panel was not opening or closing anymore. I guess we all just took it for granted the team had just left it on the ground when they saw us descending. The pilot did an excellent job and placed the nose of the UH-1F right on top of the panel.”

“We had just heard enough to know this was a hot extraction, so Jim and I were ready on the trigger with our M-60s. I remember looking for the team when we landed, but I didn’t see anyone but a soldier in a pith helmet at about 30 yards off our nose in the 11 o’clock position. I actually thought it was one of the Montagnard team members who had perhaps captured an NVA pith helmet as a war trophy. They often did this and particularly so on SFC Shriver’s recon missions.”

“I know there was an uncomfortable pause for close to a minute or so it seemed, when nothing happened. The team didn’t move. It was like there was no one outside the helicopter except the lone soldier with the pith helmet holding an AK-47, and he was appeared frozen in place under a spell. The spell broke quickly when our co-pilot growing impatient motioned for the soldier off our nose to get on the helicopter. The soldier responded quickly by firing his AK-47 right down the nose of our aircraft. The splintering Plexiglass of the windshield nearly blinded our co-pilot, and the Plexiglas flecked off into his shoulders and lower arms.

“When this happened, I pulled the trigger and managed to get off a couple rounds in the direction of the apparent NVA soldier. No sooner had I done this, I was struck twice in the lower left side of my ballistic helmet. The impact of the AK-47 armor piercing rounds knocked me directly to the floor of the helicopter. I remember being down on the floor and in a daze. How much time passed, I do not know, but it must have been only seconds. I recall hearing a very clear voice with no static and no background noise saying, “Ron, you’re not hurt, but if you don’t get up and start firing, you will be.” I listened to the voice, and got up immediately! I started firing about four feet off the ground in a tail to nose pattern, and I continued firing until I emptied my ammo can. This was about 450 rounds, and when we had lifted off without the team and just cleared the tops of the trees surrounding the LZ, I was out of ammo. I went immediate for my M-16, but I realized there was no need since we had cleared the LZ, and we were headed toward Duc Co.”

“I felt so bad about not getting the team out. I remember the pilot asking us if we are all right. We all said yes, but he knew we had been hit and the aircraft had taken several rounds. The co-pilot got the worst of it. Jim O’Goreman had been hit just above his left kidney by grazing fire, and I had a grazing scalp wound thanks to the ballistic helmet. My helmet was about two sizes too large for me, and it came right down to my eyebrows. Otherwise, a properly fitted helmet would have resulted in my being shot directly in the head about one inch above my left eyebrow. The first bullet entered the helmet and followed its curvature trapped between the layers of fiberglass. The bullet travelled [sic] about five inches in the curvature. I was told later by a Bell Helicopter Tech Rep this was equivalent to travelling [sic] through five inches of solid fiberglass. All I know is, it worked! Back at Duc Co, I took my helmet off, and the bullet with its copper jacket just fell out of my helmet. I still have it to this day. The second bullet had glanced off my helmet as I was knocked backwards, and it went through the roof of the helicopter cabin.”

“Jim and I were so hyped up we didn’t realize anything until we got back to Duc Co. Neither he nor I wore the ceramic back plates. We sat on them instead. After this mission, all that changed. He would have escaped with most likely no wound at all had he worn his plate. The poor co-pilot got the worst of it, but he could have avoided some facial scarring if his flight helmet visor would have been down. He had raised it to better look for the flasher panel and observed the team.”

“The biggest surprise of all was to find the team landing right behind us at Duc Co. I can remember running over to their helicopter and them running towards us. In a matter of minutes, a crowd was all around us, and SFC Jerry M. Shriver was all smiles as he explained what had happened. I think I never remember him talking so much. He explained, “The team received immediate contact within a minute of exiting the helicopter. Apparently, we had inserted them in the middle of a company-sized NVA unit that was dispersed around the wooded perimeter of the LZ. Once our helicopter had lifted off, the dumb struck NVA realized what had happened, and they started firing at the team. The call was placed for extraction, and a Montagnard team member began flashing the orange panel. He opened and closed it twice only to catch two bullets in it. This is when he threw it on the ground for us to land on.”

“SFC Shriver began moving the team to the rear of the LZ in the only direction they were not taking fire. In a matter of minutes, the NVA started charging his position. Everything ceased as we approached the LZ, and we landed in between the NVA and the team. This gave the team a momentary break in the shooting to run for a second helicopter slick behind us to pick up the team. Having no radio, we had no idea a second slick was behind us. Our action so startled the NVA company, they crouched in misbelief as we practically landed on top of them.”

“With the spell broken, all hell broke loose again as Shriver was getting his team on the second slick. Looking back at us, he knew we were in big trouble. He told me, ‘When I saw you go down I thought you were a goner, but you got up in less than a minute and started firing. When you went down, about 15 NVA charged the helicopter from your side. I really think they wanted to capture it. But, when you stood up, they all fell to their death. At any rate, how do you feel about killing 15 praying men because that is what you did?’ I told him, ‘I didn’t see a thing other than the lone NVA that was the spell breaker.’ I do know 15 rounds went through our helicopter with the majority coming from the left and front of the airframe.”

“Shriver had something for show and tell too, like my helmet everyone was asking to see. As normal, he was the last of his team to enter the slick behind us. Just as he climbed aboard, he felt something hit him in the back. The impact actually helped him board quicker. To his amazement, he found after they had cleared the LZ, his M-9 45- caliber grease gun had been struck by an enemy bullet in the magazine receiver area and penetrating the magazine while lodge between two cartridges without causing them to fire. He had thrown the slung M-9 over his shoulder while he threw out both hands to board the helicopter. If he had left the weapon slung to his side, he would have been shot dead in the middle of his back.”

“Later that evening back at Ban Me Thuot, I felt a tremendous honor when SFC Jerry “Mad Dog” Shriver invited me over to his table at the CCS camp’s NCO Club to have a beer with him. He thanked me for my actions, and we both celebrated our good luck. About that voice I heard, no one of that crew spoke to me at that time. I can tell you it wasn’t my voice I heard. I’m eternally grateful I listened to the Celestial Voice.”

“Our pilot received the Silver Star for that mission, and he deserved it. The co-pilot received the DFC for Heroism and a Purple Heart, and Jim O’Goreman and I received the same two medals for the mission. Later, in March of 1969, Jim O’Goreman would receive a second Purple Heart for wounds he received in a crash that took eight lives including the Commander of the 20th SOS, LTC Frank A. DiFiglia.”

This appears this is one of the earliest missions Shriver ran after being transferred from Exploit Company back to Recon Company again. Unfortunately Ron Winkles could not remember the name of his co-pilot, as they often changed planes almost daily, but the CE/Gunner generally stayed with the same bird Ron Winkles said, “I flew a dozen missions or more with Jerry Shriver and most of them went without special citation. After the Nov. 4 mission, Shriver warmed up to me a little. He invited me to sit with him in the NCO club at BMT a couple times. I recall playing chess with him for a couple minutes. Of course, he beat the hell out of me. I always let him do most of the talking, and he told me some very interesting stories.” A lot of men like to brag about serving with the famed SFC Jerry “Mad Dog” Shriver. Most often, they are just ‘wannabees.’ Winkles is the real deal, as fortunately we have Shriver’s BSV award citation to match Winkles’ report of the mission. Winkles has his performance report citing the mission, as well as a letter from MAJ Richard D. Cox who was the pilot on the mission. An article was released through the AP on his helmet episode and it was printed in the Stars and Stripes back in November 1968. Winkles still brings those two NVA bullets that hit his helmet to proudly display at the Green Hornet reunions.

Jerry Shriver’s Recon Missions with Valor Awards

On April 24, 1969, CCS Recon Team Hatchet Force initiated a direct attach on the North Vietnamese headquarters known as the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN). One of the most compete stories of this complex mission are noted from the following descriptions from a Task Force Omega web site on MIAs authored by Patty Hopper who did extensive research on the mission, including interviews with LTC Earl Trabue, the CCS CO and an eyewitness to the entire scenario.

“During 1968 and early 1969, CCS had been inserting 6-man reconnaissance patrols into the Fish Hook border area between South Vietnam and Cambodia. The hard reality was due to the intense enemy presence continuously operating in the region, if a patrol could be inserted and stay on the ground undetected for three days, it was very lucky. Many teams were discovered within 30 minutes of insertion and were forced to be extracted under fire shortly thereafter. Another major factor faced by reconnaissance teams, including the Hatchet Force, was locating an unguarded landing zone (LZ). Locating one large enough for a single helicopter insertion was one thing, however, finding an unguarded LZ large enough to accommodate four helicopters was quite another.”

“To shift the balance of power and disrupt the NVA’s influence in the region, a direct attack on the North Vietnamese headquarters for operations in South Vietnam known as the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN) was developed by the J2 of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. The headquarters bunker complex was located just over a mile inside Cambodia in the Fish Hook area; approximately 14 miles southeast of Memot, Cambodia; 20 miles southeast of Quan Loi and 28 miles northeast of Tay Ninh, South Vietnam.”

“After receiving his mission several days before the Hatchet Force were to be inserted, LTC Earl Trabue, Commander of CCS, informed OP-35, MACV-SOG that in his opinion their plan to attack the COSVN complex was not viable. The plan included the Hatchet (Exploitation) Force snatching NVA prisoners as well as reporting on the effects of a B-52 ArcLight air strike against the COSVN complex that was also going to be used to cover the team’s insertion. LTC Trabue fully understood the complexities of the mission and believed it to be too dangerous to insert only an augmented platoon and should be cancelled. Further, he believed the B-52 ArcLight air strike would not stun the enemy as projected.”

“The size of the Hatchet Force was limited as only nine US Army Huey helicopters assigned to the 195th Assault Helicopter Company were available for the 10 minute, 20-mile flight from Quan Loi Airfield, MACV-SOG’s southern launch site, to the target – four Huey transport insertion helicopters supported by four Huey gunships and one Huey command and control aircraft for directing the overall mission. Because of the flight configuration, only one platoon-sized force could be assigned to this mission.”

“The night before the mission, our CCS Medic SGT Jamison and a fellow New Yorker – WO Dave Mazoff, a 195th AHC pilot, shared a few quiet moments. Mazoff recalls, “I was on the mission that SGT Jamison was KIA. We met in my tent with a group of pilots and SF guys the night before the mission. We all knew it was going to be hot and I will always remember SGT Jamison telling me he did not have a good feeling about coming out. I told him not to worry, that we were there to make sure he made it out. I was wrong. We were both from New York and hit it off. I remember him telling me he wanted to go back to school and become a doctor when he got back to the world. I have a photo of him and me taken the day before he was killed on the mission in the ‘Fishhook’.”

Henry Kohn of the MLS Signal Section recalls, “Just before the mission one night, I was standing next to the TOC talking to Joe Farrar and the launch site was mortared. Joe took shrapnel in his arm and it put him out of commission for the mission- he wanted to treat the wound and go any-way – but they told him to stand down. Another medic Ernie Jamison (who was with me in Sigma) had just returned from R&R in Hawaii and they told him that he was going in Joe’s place. Ernie was really excited about it – up until that point he had only flown chase medic and had never been on the ground. His father was a neurosurgeon in Philadelphia I think and his family had a long line of doctors. But when he came back and showed me the pictures of his little girl that was born while he was away, he was a new man. And when they told him to pack for the mission he and Joe put the medical kit together and they stayed up late while Joe briefed him on what had happened in his absence. I don’t think anyone got much sleep that night.

Hopper and Trabue continue, “All US Army helicopters were under the operational control of the 195th AHC air mission commander, LT Bill Aubuchon, in the command and control helicopter. The only other air asset assigned to this mission was an Air Force FAC who was to call for and coordinate fixed wing air assets should their participation be necessary.”

“Shortly before takeoff at dawn, SFC Shriver boarded the first helicopter. As the aircraft lifted off the ground for the flight, the B-52s were to be making final preparations for their bomb run against COSVN. At the same time the helicopters prepared to takeoff, the Huey carrying CPT O’Rourke and five team members developed mechanical problems and was forced to abort the mission. Because of this, CPT Cahill, the assistant ground commander, took over the responsibilities of ground commander for the remainder of the mission.”

“The original plan was for the helicopters to insert the team as the air strike’s dust settled. Unfortunately, when the helicopters arrived at the designated coordinates, it was the wrong location. The aircraft flew around for 30 to 45 minutes searching for signs of dry bomb craters, which would mark the correct site. When the pilots finally found three dry ones, the helicopters descended in-trail toward them and landed. After the members of the Hatchet Force leaped off, the helicopters’ pulled up and away from the landing zone (LZ) for their return flight to Quan Loi.”

“As soon as the landing force was on the ground, the men took cover in one of two craters located side by side and roughly 30 to 50 yards from the bunker complex. Immediately after discharging their passengers, the helicopters pulled up and away from the LZ. They had reached an altitude of only 20 feet above the ground when the NVA opened fire from concrete bunkers and entrenched positions with a withering barrage of gunfire wounding or killing those men who had not reached the safety of the craters.”

“From his position in the western-most bomb crater, Jerry Shriver radioed other team members stating that a machine gun bunker to his left front had his men pinned down and asked if anyone could fire at it to relieve the pressure. CPT Cahill, 1LT Marcantel and SGT Ernest C. Jamison, who had taken cover in the center crater, reported they were also pinned down and unable to help. The air commander notified the Hatchet Force that he was bringing in the gunships for air support. Immediately he directed all gunships to use their mini-guns and rockets to attack the NVA positions. Further, to make sure no short rounds or bombs hit our troops, all attack passes were made along the bunker line, not head on into it. As the aircraft made their attack passes, one of the door gunners noted that the bunkers were made of concrete.”

“From his vantage point overhead, MAJ Benjamin T. Kapp, Jr., the southern launch site’s senior launch officer who was also in the command and control aircraft as coordinator to assist CCS Cmdr. LTC Trabue should the situation necessitate it, observed the battle site. From his vantage point, MAJ Kapp could see the platoon members in the bomb craters. According to one report, he witnessed North Vietnamese machine guns firing into the bodies of the men lying in front of the enemy positions. These machine guns also covered the open ground covered in ankle-high brown grass with grazing fire effectively trapping the members of the exploitation platoon.”

“Approximately 10 to 15 minutes into the raging battle, CPT Cahill heard SFC Shriver transmit over his radio that he and five Montagnard soldiers were going to enter the tree line on the west edge of the LZ in an effort to flank an enemy position. Paul Cahill observed the six men as they broke from the crater and ran across the 30 yards of open ground between the crater and the tree line. As the men raced through the low grass toward the trees, Jerry Shriver maintained radio contact with the command and control aircraft and CPT Cahill continued to monitor their progress.”

“As he watched, Paul Cahill saw SFC Shriver being struck by several rounds of automatic weapons fire at the tree-line and fall to the ground. At the same time, radio contact between Jerry Shriver and the command aircraft was severed in mid-sentence. During the remainder of the mission several attempts were made to re-establish radio contact with the exploitation platoon leader, however, all attempts failed. Later Paul Cahill reported he believed ‘Jerry Shriver was dead when he hit the ground’.”

Of the 18 men inserted for the mission and the six later inserted in support of the Hatchet Force, only some of the members of the recon team were recovered uninjured. Of the original 18 members of the Hatchet Force, 10 were wounded and safely evacuated. Greg Harrigan’s remains were recovered, Ernest Jamison was reported as Killed in Action/Body Not Recovered, and Jerry Shriver, along with his five Montagnards, was reported as Missing in Action.

After the Exploitation platoon was decimated, other Special Forces personnel assigned to Command and Control North were listening to a North Vietnamese propaganda broadcast made by “Hanoi Hanna” when they heard her boast that “Mad Dog Shriver had been captured” by NVA forces. A second broadcast aired by Hanoi Hanna some time after the first stated that “they had Shriver’s ears,” which was a euphemism for Jerry Shriver being dead and the NVA had his body. The first broadcast was later substantiated by a US military intelligence report declassified in 1993 that acknowledged “Vietnamese voices were later heard (which) stated that one American was in the process of being captured.”

Missing in Action/Body Never Recovered 4/24/1969

Rest in Peace: Special Forces Commander Jerry M. Shriver was 27 years old and his home of record was Sacramento, Calif. He was just weeks from finishing his third year in South Vietnam. Shriver was carried as Missing In Action until 06/10/74, when the Secretary of the Army approved a Presumptive Finding of Death. During this time he was promoted from E-7 to E-8. Today one can visit the South Walton County, Florida Court-House Annex. Jerry is honored there, along with the other fallen warriors of Walton County, at the entrance of the Annex. This was Jerry’s home county at some time. Also, another CCS Recon man, 1LT Randy Harrison, recently reported that “in one of the most unlikely experiences of my life, last summer I literally stumbled on a marker erected in his memory in the Fort Lawton cemetery here near his Seattle. I visit it often.” The Shriver marker is at Plot 4-235, placed 08/22/1974. Shriver’s name location on THE WALL is Panel 36W, Row 41.