MACV-SOG's Black Programs

Project Eldest Son

During the Vietnam War, the Studies And Observations Group (SOG) created an ingenious top-secret program called Project Eldest Son to wreak general mayhem and cause the Viet Cong and NVA to doubt the safety of their guns and ammunition.

Amid a firefight near the Cambodian border on June 6, 1968, a North Vietnamese Army soldier spotted an American G.I. raising his rifle, and the NVA infantryman pulled his trigger, anticipating a muzzle blast. He got a blast, alright, but not quite what he’d expected.

United States 1st Infantry Division troops later found the enemy soldier, sprawled beside his Chinese Type 56 AK, quite dead – but not from small-arms fire. Peculiarly, they could see, his rifle had exploded, its shattered receiver killing him instantly. It seemed a great mystery that his AK had blown up since nothing was blocking the bore. Bad metallurgy, the G.I.s concluded, or possibly defective ammo. It was neither.

In reality, this actual incident was the calculated handiwork of one the Vietnam War’s most secret and least understood covert operations: Project Eldest Son. So secret was this sabotage effort that few G.I.s in Southeast Asia ever heard of it or the organization behind it, the innocuously named Studies and Observations Group. As the Vietnam War’s top-secret special ops task force, SOG’s operators – Army Special Forces, Air Force Air Commandos and Navy SEALs – worked directly for the Joint Chiefs, executing highly classified, deniable missions in the enemy’s backyard of Laos, Cambodiaand North Vietnam.

The genesis of Eldest Son was the fertile mind of SOG’s commander, 1966-68, Colonel John K. Singlaub, a World War II veteran of covert actions with the Office of Strategic Services. “I was frustrated by the fact that I couldn’t airlift the ammunition we were discovering on the [Ho Chi Minh] Trail” in Laos, Singlaub explained. It was not unusual for SOG’s small recon teams – composed of two or three American Green Berets and four to six native soldiers – to find tons of ammunition in enemy base camps and caches along the Laotian highway system. But SOG teams lacked the manpower to secure the sites or carry the ordnance away. Further, it could not be burned up, and demolition would only scatter small-arms ammunition, not destroy it. “Initially I thought of just boobytrapping it so that when they’d pick up a case it would blow up,” Singlaub recalled. Then it hit him – boobytrap the ammunition itself!

Though obscure, this trick was not new. In the 1930s, to combat rebellious tribesmen in northwest India’s Waziristan – the same lawless region where Taliban and al Qaeda terrorists hide today – the British army planted sabotaged .303 rifle ammunition. Even before that, during the Second Metabele War (1896-97) in today’s Zimbabwe, British scouts (led by the American adventurer Frederick Russell Burnham) had slipped explosive- packed rifle cartridges into hostile stockpiles, to deadly effect. SOG would do likewise, the Joint Chiefs decided on August 30, 1967, but first Col. Singlaub arranged for CIA ordnance experts to conduct a quick feasibility study. A few weeks later, at Camp Chinen, Okinawa, Singlaub watched a CIA technician load a sabotaged 7.62×39 mm cartridge into a bench-mounted AK rifle. “It completely blew up the receiver and the bolt was projected backwards,” Singlaub observed, “I would imagine into the head of the firer.”

After that success began a month of tedious bullet pulling to manually disassemble thousands of 7.62 mm cartridges, made more difficult because Chinese ammo had a tough lacquer seal where the bullet seated into the case. In this process, some bullets suffered tiny scrapes, but when reloaded these marks seated out of sight below the case mouth. Rounds were inspected to ensure they showed no signs of tampering. When the job was done, 11,565 AK rounds had been sabotaged, along with 556 rounds for the Communist Bloc’s heavy 12.7 mm machine gun, a major anti-helicopter weapon.

Eldest Son cartridges originally were reloaded with a powder similar to PETN high explosive, but sufficiently shock-sensitive that an ordinary rifle primer would detonate it. This white powder, however, did not even faintly resemble gunpowder. SOG’s technical wizard, Ben Baker – our answer to James Bond’s “Q” – decided this powder might compromise the program if ever an enemy soldier pulled apart an Eldest Son round. He obtained a substitute explosive that so closely resembled gunpowder that it would pass inspection by anyone but an ordnance expert. While the AKM and Type 56 AKs and the RPD light machine gun could accommodate a chamber pressure of 45,000 p.s.i., Baker’s deadly powder generated a whopping 250,000 p.s.i.

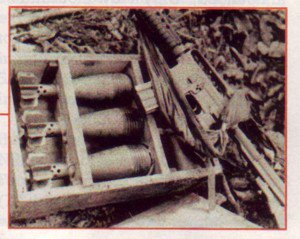

Sabotaging the ammunition proved the easiest challenge. The CIA’s Okinawa lab also did a very professional job of prying open ammo crates, unsealing the interior metal cans and then repacking them so there was no sign of tampering. In addition to SOG sabotaging 7.62 mm and 12.7 mm rounds, these CIA ordnance experts perfected a special fuse for the Communist 82 mm mortar round that would detonate the hand-dropped projectile while inside the mortar tube, for especially devastating effect. Exactly 1,968 of these mortar rounds were sabotaged, too.

Project Eldest Son’s greatest challenge was “placement” – getting the infernal devices into the enemy logistical system without detection. That’s where SOG’s Green Beret-led recon teams came in. Since the fall of 1965, our small teams had been running deniable missions into Laos to gather intelligence, wiretap enemy communications, kidnap key enemy personnel, ambush convoys, raid supply dumps, plant mines and generally make life as difficult as possible in enemy rear areas. As an additional mission, each team carried along a few Eldest Son rounds – usually as a single round in an otherwise full AK magazine or one round in an RPD machine gun belt or a sealed ammo can – to plant whenever an opportunity arose.

When an SOG team discovered an ammo dump, they planted Eldest Son; when a SOG team ambushed an enemy patrol, they switched magazines in a dead soldier’s AK. It was critically important never to plant more than one round per magazine, belt or ammo can, so no amount of searching after a gun exploded would uncover a second round, to preclude the enemy from determining this was sabotage.

Planting sabotaged 82 mm mortar ammo proved more cumbersome because these were not transported as loose rounds, but in three-round, wooden cases. Thus, you had to tote a whole case, which must have weighed more than 25 lbs. Twice I recall carrying such crates for insertion in enemy rear areas, and to our surprise, my team once witnessed a platoon of NVA soldiers carry one away. SOG’s most clever insertion was accomplished by SOG SEALS operating in the Mekong Delta, where they filled a captured sampan with tainted cases of ammunition, shot it tastefully full of bullet holes, then spilled chicken blood over it and set it adrift upstream from a known Viet Cong village. Of course, the VC assumed the boat’s Communist crew had fallen overboard during an ambush. The Viet Cong took the ammunition, hook, line and sinker.

In Laos, American B-52s constantly targeted enemy logistical areas, which churned up sizeable pieces of terrain. SOG exploited this opportunity by organizing a special team that landed just after B-52 strikes to construct false bunkers in such devastated tracts, then “salt” these stockpiles with Eldest Son ammunition. However, on November 30, 1968, the helicopter carrying SOG’s secret Eldest Son team, flying some 20 miles west of the Khe Sanh Marine base, was hit by an enemy 37 mm anti-aircraft round, setting off a tremendous mid-air explosion. Seven cases of tainted 82 mm mortar ammunition detonated, killing everyone on board, including Maj. Samuel Toomey and seven U.S. Army Green Berets. Their remains were not recovered for 20 years.

But as a result of these cross- border efforts, Eldest Son rounds began to turn up inside South Vietnam. In a northern province, 101st Airborne Division paratroopers found a dead Communist soldier grasping his exploded rifle, while an officer at SOG’s Saigonheadquarters, Captain Ed Lesesne, received the photo of a dead enemy soldier with his bolt blown out the back of his AK. “It had gone right through his eye socket,” Lesesne reported.

Chad Spawr, an intelligence specialist with the 1st Infantry Division, heard of such a case but, “didn’t believe it until they walked me over and opened up the body bag, and there he was, with the weapon in the bag.” Unaware of SOG’s covert program, Spawr attributed the incident to inferior weapons and ammo.

Boobytrapped mortar rounds took their toll, too. Twenty-Fifth Infantry Division soldiers came upon an entire enemy mortar battery destroyed – four peeled back tubes with dead gunners. In another incident, a 101st Airborne firebase was taking mortar fire when there was an odd-sounding, “boom-pff!” A patrol later found two enemy bodies beside a split mortar tube and blood trails going off into the jungle. On July 3, 1968, after an enemy mortar attack on Ban Me Thuot airstrip, nine Communist soldiers were found dead in one firing position, their tube so badly shattered that it had vanished but for two small fragments.

Boobytrapped ammunition clearly was getting into enemy hands, so it was time to initiate SOG’s insidious “black psyop” exploitation. “Our interest was not in killing the soldier that was using the weapon,” explained Colonel Steve Cavanaugh, who replaced Singlaub in 1968. “We were trying to leave in the minds of the North Vietnamese that the ammunition they were getting from China was bad ammunition.” Hopefully, this would aggravate Hanoi’s leadership – which traditionally distrusted the Chinese – and cause individual soldiers to question the reliability (and safety) of their Chinese-supplied arms and ordnance.

One Viet Cong document – forged by SOG and insinuated into enemy channels through a double-agent – made light of exploding weapons, claiming, “We know that it is rumored some of the ammunition has exploded in the AK-47. This report is greatly exaggerated. It is a very, very small percentage of the ammunition that has exploded.”

Another forged document announced, “Only a few thousand such cases have been found thus far,” and concluded, “The People’s Republic of China may have been having some quality control problems [but] these are being worked out and we think that in the future there will be very little chance of this happening.”

That, “in the future,” hook was especially devious, because an enemy soldier looking at lot numbers could see that virtually all his ammo had been loaded years earlier. No fresh ammo could possibly reach soldiers fighting in the South for many years.

Next came an overt “safety” campaign, with Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) publishing Technical Intelligence Brief No. 2-68, “Analysis of Damaged Weapons.” Openly circulated to U.S. and South Vietnamese units, this SOG-inspired study examined several exploded AKs, concluding they were destroyed by “defective metallurgy resulting in fatigue cracks” or “faulty ammunition, which produced excessive chamber pressure.” An SOG operative left a copy at a Saigon bar whose owners were suspected enemy agents.

Under the guise of cautioning G.I.s against using enemy weapons, warnings were sent to Armed Forces Radio and TV. The civilian Stateside tabloid Army Times warned, “Numerous incidents have caused injury and sometimes death to the operators of enemy weapons,” the cause of which was, “defective metallurgy” or “faulty ammo.” The 25th Infantry Division newspaper similarly warned soldiers on July 14, 1969, that, “because of poor quality control procedures in Communist Bloc factories, many AKs with even a slight malfunction will blow up when fired.” Despite such warnings, some G.I.s fired captured arms, and inevitably one American’s souvenir AK exploded, inflicting serious (but not fatal) injuries.

That incident spurned SOG itself to stop using captured ammunition in our own AKs and RPD machine guns. SOG purchased commercial 7.62 mm ammunition through a Finnish middleman – and, ironically, this ammo, which SOG’s covert operators fired at their Communist foes – had been manufactured in a Soviet arsenal in Petrograd.

By mid-1969, word about Eldest Son began leaking out, with articles in the New York Times and Time, compelling SOG to change the codename to Italian Green, and later, to Pole Bean. As of July 1, 1969, a declassified report discloses, SOG operatives had inserted 3,638 rounds of sabotaged 7.62 mm, plus 167 rounds of 12.7 mm and 821 rounds of 82 mm mortar ammunition. That fall, the Joint Chiefs directed SOG to dispose of its remaining stockpile and end the program. In November, my team was specially tasked to insert as much Eldest Son as possible, making multiple landings on the Laotian border to get rid of the stuff before authority expired.

Lacking the earlier finesse, such insertions had to have confirmed to the enemy that we were sabotaging his ammunition-but even this, SOG believed, was psychologically useful, creating a big shell game in which the enemy had to question endlessly which ammunition was polluted and which was not. The enemy came to fear any cache where there was evidence that SOG recon teams got near it and, thanks to radio intercepts, SOG headquarters learned that the enemy’s highest levels of command had expressed concerns about exploding arms, Chinese quality control and sabotage. In that sense, Project Eldest Son was a total success – but as with any such covert deception program, you can never quite be sure.

Major John L. Plaster, USAR (Ret.). Wreaking Havoc One Round At A Time. American Rifleman. May 2008. |