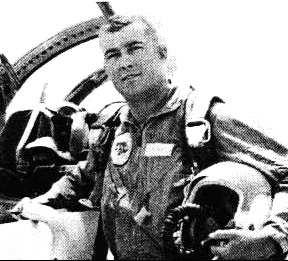

Henry Lewis Allen

Name: Henry Lewis Allen

Rank/Branch: O2/US Air Force

Unit: 56th Special Operations Wing, Udorn AF TH (RAVENS)

Date of Birth: 21 September 1943

Home City of Record: Daytona Beach FL

Date of Loss: 26 March 1970

Country of Loss: Laos

Loss Coordinates: 175900N 1023400E (TF543931)

Status (in 1973): Missing in Action

Category: 4

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: O1

Other Personnel in Incident: Richard G. Elzinga (missing)

Refno: 1579

Source: Compiled by Homecoming II Project 15 March 1990 with the assistance of one or more of the following: raw data from U.S. Government agency sources, correspondence with POW/MIA families, published sources, interviews. Updated by the P.O.W. NETWORK. 2020

REMARKS:

SYNOPSIS: The Steve Canyon program was a highly classified FAC (forward air control) operation covering the military regions of Laos. U.S. military operations in Laos were severely restricted during the Vietnam War era because Laos had been declared neutral by the Geneva Accords.

The non-communist forces in Laos, however, had a critical need for military support in order to defend territory used by Lao and North Vietnamese communist forces. The U.S., in conjunction with non-communist forces in Laos, devised a system whereby U.S. military personnel could be “in the black” or “sheep-dipped” (clandestine; mustered out of the military to perform military duties as a civilian) to operate in Laos under supervision of the U.S. Ambassador to Laos.

RAVEN was the radio call sign which identified the flyers of the Steve Canyon Program. Men recruited for the program were rated Air Force officers with at least six months experience in Vietnam. They tended to be the very best of pilots, but by definition, this meant that they were also mavericks, and considered a bit wild by the mainstream military establishment.

The Ravens came under the formal command of CINCPAC and the 7/13th Air Force 56th Special Operations Wing at Nakhon Phanom, but their pay records were maintained at Udorn with Detachment 1. Officially, they were on loan to the

U.S. Air Attache at Vientiane. Unofficially, they were sent to outposts like Long Tieng, where their field commanders were the CIA, the Meo Generals, and the U.S. Ambassador. Once on duty, they flew FAC missions which controlled all U.S. air strikes over Laos.

All tactical strike aircraft had to be under the control of a FAC, who was intimately familiar with the locale, the populous, and the tactical situation. The FAC would find the target, order up U.S. fighter/bombers from an airborne command and control center, mark the target accurately with white phosphorus (Willy Pete) rockets, and control the operation throughout the time the planes remained on station. After the fighters had departed, the FAC stayed over the target to make a bomb damage assessment (BDA).

The FAC also had to ensure that there were no attacks on civilians, a complex problem in a war where there were no front lines and any hamlet could suddenly become part of the combat zone. A FAC needed a fighter pilot’s mentality, but but was obliged to fly slow and low in such unarmed and vulnerable aircraft as the Cessna O1 Bird Dog, and the Cessna O2. Consequently, aircraft used by the Ravens were continually peppered with ground fire. A strong fabric tape was simply slapped over the bullet holes until the aircraft could no longer fly.

Ravens were hopelessly overworked by the war. The need for secrecy kept their numbers low (never more than 22 at one time), and the critical need of the Meo sometimes demanded each pilot fly 10 and 12 hour days. Some Ravens

completed their tour of approximately 6 months with a total of over 500 combat missions.

The Ravens in at Long Tieng in Military Region II, had, for several years, the most difficult area in Laos. The base, just on the southern edge of the Plain of Jars, was also the headquarters for the CIA-funded Meo army commanded by General Vang Pao. An interesting account of this group can be read in Christopher Robbins’ book, “The Ravens”. This book contains an account of the loss of 1Lt. Henry L. Allen and Capt. Richard G. Elzinga:

The post at Long Tieng had been under seige, and it became necessary for Ravens to live in Vietntiane in new quarters nicknamed Silver City, but they continued to stage out of Long Tieng. “They called the daily flight there and back…the ‘commute.’

“Hank Allen, an exceptional pilot with eyes like a hawk, took off with Dick Elzinga in the front seat of his O-1. Allen was ‘short’, soon to return home after a tour in which he had notched up four hundred combat missions, and he planned to return directly to the States and marry his fiancee within a fortnight. Elzinga had only just arrived in Laos, and it was his first trip up to the secret city. Allen intended to use the ‘commute’ as a checkout ride. It was a cloudy day. He took off and reported over the radio…that the O-1 was airborne. It was the last thing ever heard from them. Neither of the pilots, nor the plane, was ever seen again.

“They had disappeared. Each of the Ravens spent at least two hours, on top of their usual day’s flying, searching for the wreckage. No Mayday call had been heard, nor had a beeper signal been picked up from the survival radio, and no clue to the airplane’s whereabouts was discovered. The disappearance was a complete mystery.”

The official point of loss was noted as 20 miles northeast of Vientiane, Laos. Both men were classified Missing in Action.

Three years later, on March 10, 1973, a Pathet Lao agent was captured carrying three of Elzinga’s traveler’s checks and money of three countries. Elzinga had not been in Vientiane long enough to get a locker for his billfold. According to a 1974 list compiled by the National League of POW/MIA Families, Elzinga, at least, survived the loss of the O1 plane.

Elzinga and Allen are among nearly 600 Americans lost in Laos. Even though the Pathet Lao stated publicly that they held “tens of tens” of American prisoners, not one American held in Laos was ever released — or negotiated for